Back to Table of Contents

BEHAIM informs us in one of the legends of his globe that his work is based upon Ptolemy's Cosmography, for the one part, and upon the travels of Marco Polo and Sir John Mandeville, and the explorations carried on by the order of King John of Portugal, for the remainder. Other sources were, however, drawn upon by the compiler, and several of these are incidentally referred to by him or easily discoverable, but as to a considerable part of his design I have been unable to trace the authorities consulted by him.

With respect to Ptolemy, Behaim has been guided by the opinion of the "orthodox" geographers of his time and has consequently copied the greater part of the outline of the map of the world designed by the great Alexandrian. He has, however, rejected the theory of the Indian ocean being a "mare clausum," and although he accepted Ptolemy's outline for the Mediterranean, the Black Sea and the Caspian, he substituted modern place names for most of those given by ancient geographers. The edition of Ptolemy of which he availed himself was that published at Ulm in 1482, and reprinted in 1486, with the maps of Dominus Nicolaus Germanus.

Isidor of Seville, or one of his numerous copyists, is the authority for placing the islands of Argyra, Chryse and Tylos far to the east, to the south of Zipangu, as also for a reference to syrens and other monsters of the eastern ocean. Behaim, in a legend (M 7) refers for further information on this subject to Pliny, Aristotle, Strabo and the `Specula' of Vincent of Beauvais.(3) The last, however, merely copied Isidor, whilst the others named did not believe in these monstrosities.

If the reader examines Map 2, where the information derived from Marco Polo is printed in red, he cannot fail to be struck by the extent to which the author of the globe is indebted to the greatest among mediæval travellers. Accounts, in MS., of Polo's travels in Latin, French, Italian and German, were available at the time the globe was making at Nuremberg, as also three printed editions. The earliest of these, in German, had appeared in 1477 at Nuremberg;(5) a Latin version, from a translation made by Friar Francisco Pipino of Bologna in 1320, had been published at Antwerp in 1485;(6) and an Italian version printed at Venice by Z. Bapt. da Sessa in 1486. Neither the German nor the Italian version is divided into books and chapters. Pipino's Latin version, on the other hand, is divided in this manner, and Behaim in seven of his legends quotes these divisions correctly. We should naturally conclude from this that this was the version consulted if on other occasions he had not quoted the chapters as given in the version which was first printed in Ramusio's `Navigationi e viaggi' in 1559.(7) If we add that many proper names are spelt sometimes according to Pipino's version and at others according to that of Ramusio, and that in several instances names are inserted twice upon the globe and separated by hundreds of miles, we may fairly conclude that we have not before us an original compilation, but an uncritical combination of two separate maps designed to illustrate Marco Polo's travels, whose authors, not being skilled cartographers, differed widely as to the localisation of the places visited or described by the Venetian traveller. Two instances of this duplication of place names may be referred to. Bangala, the well-known province at the mouth of the Ganges, is placed once in the very centre of Cathai (K 43) and a second time to the east of the Indus (G 15), both positions being absolutely erroneous. Vocan (Wakhan) likewise appears twice, once in Bactriana (G 39) (which is fairly correct), and a second time to the east of the Ganges (H 26). Instances of such duplication might be multiplied.

I have thought it worth while to plot the routes travelled or described by Marco Polo in order to exhibit at a glance the seriously incorrect delineation of Eastern Asia on Behaim's globe, and in the maps of his contemporaries and successors, whose authors may have been "men of science," but who certainly were most incompetent cartographers.

In plotting Marco Polo's routes I start from Ormus (Armuza). I accept Ptolemy's latitude for that place (23°30'), but not his longitude. Assuming the Straits of Gibraltar (Herculeum Fretum) to lie four degrees to the east of Lisbon, the meridian difference between the Straits and Beirut to amount to 41 degrees, as warranted by the examination of the Portolano charts, Beirut would be situated in longitude 45° east of Lisbon. Adding 28 degrees for the difference of longitude between Beirut and Ormus (according to Ptolemy), I locate the latter 73 degrees to the east of Lisbon.

Starting from Ormus I plotted the routes of Marco Polo, as described in his narrative, as carefully as possible, and without allowing myself to be biased by information brought home by earlier or later travellers. Twenty Roman miles have been allowed for each day's land journey, and the result is shown on Map 3. A comparison of this sketch with Behaim's globe, or indeed with other maps of the period, even including Schöner's globe of 1520,(8) shows clearly that a much nearer approach to a correct representation to the actual countries of Eastern Asia could have been secured had these early cartographers taken the trouble to consult the account which Marco Polo gave of his travels. India would have stood out distinctly as a large peninsula. Ceylon though unduly magnified would have occupied its correct position, and the huge peninsula beyond Ptolemy's "Furthest," a duplicated or bogus India,(9) would have disappeared, and place names in that peninsula, and even beyond it, such as Murfuli, Maabar, Lac or Lar, Cael, Var, Coulam, Cumari, Dely, Cambaia, Servenath, Chesmakoran and Bangala would have occupied approximately correct sites in Polo's India maior.

Marco Polo's account is perfectly clear as to the peninsular shape of India. Already at Pentam and Java minor he had lost sight of the Pole star, which proves that he then believed himself to be near the Equator, if not to the south of it. He then takes a westerly course to Maabar, sails for 500 miles to the south-west, doubles the southern extremity of India, and once more perceives the Pole Star when 30 miles beyond Cumari. Following the coast in a north-westerly direction, the star rises higher and higher, its altitude, at Guzurat, being already six cubits.

The islands which extend from Madagascar eastward as far as Candyn are named and described by Marco Polo, Candyn alone excepted, but the outlines given to them, and still less the duplicated India, cannot possibly have been copied from a map furnished or authorised by the Venetian traveller. Such a map, it is believed, was prepared in the time of Duke Francesco Dandolo (1329-39) soon after the death of Marco Polo, and it still hangs in the Sala dello Scudo of the Ducal Palace. This map, however, was renovated under the supervision of Giambattista Ramusio during the reign of Duke Francesco Donato (1545-53),(10) and even in its original state it cannot have represented the views of Marco Polo. Cambalu (Peking), for instance, which Marco Polo describes (Pipino's version II. 19,) as being situated within two days' journey of the ocean, is placed on that map more than 1,600 geographical miles inland.

The only contemporary map upon which the delineation of Eastern Asia including the place names is almost identical with that given on Behaim's globe is by Waldseemüller, and was published in 1507 (see p. 36).(11) We may conclude from this that both Behaim and Waldseemüller derived their information from the same source, unless, indeed, we are to suppose that the Lotharingian cartographer had procured a copy of the globe which he embodied in his own design. A comparison of the two shows, however, that such cannot have been the case, for there are many names upon the map which are not to be found on the globe. The source or sources of this delineation of Eastern Asia have not yet been discovered, but if we bear in mind that the outline of the Portuguese chart of 1502 published by Hamy (see p. 46) agrees with that of the globe, although its nomenclature is very poor; that on the Laon globe (see p. 57) the islands extending from Madagascar to Candyn and the duplicated India are identical with these features as shown on Behaim's globe, and that the map of Henricus Martellus (p. 67) strikingly resembles the globe in the shape given to the duplicated India, we may fairly conclude that the sources drawn upon by Behaim were equally available to his predecessors not only, but also to the author of the Portuguese chart of 1502 and to Waldseemüller. In short, neither Behaim nor any of his contemporaries took the trouble to lay down Marco Polo's routes as described by himself, which would have resulted in a map very much like that compiled by myself, but were content to accept or combine the erroneous designs of incompetent older authorities.

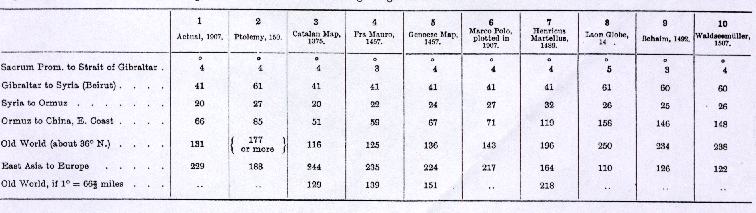

If the reader turns back a few pages, and reads my notes on the reconstruction of Marco Polo's routes, he will find that it results in a longitudinal extent of the Old World, from Lisbon to the east coast of China, of 142 degrees. According to the Catalan map of 1375 this extent amounts to 116 degrees, according to Fra Mauro (1457) to 125, according to the Genoese map of the same date to 136 degrees, the actual extent according to modern maps being 131 degrees.

Toscanelli (1474),(12) on the other hand, gives the old world a longitudinal extension of 230 degrees, thus narrowing the width of the Atlantic to 130 degrees. This encouraged Columbus to sail to the west in the confident hope of being able to reach the wealthy cities of Cipangu and Cathai. The author of the Laon globe went even further, for he reduced the width of the Atlantic to 110 degrees.

An intermediate position between these extremes is occupied by Henricus Martellus, 1489, who gives the Old World a longitudinal extent of 196 degrees.(13)

Toscanelli may be deserving of credit, for having been the first to draw a graduated map of the great Western Ocean, but when we find that he rejected Ptolemy's critique of the exaggerated extent given by Marinus of Tyre to the route followed by the caravans in their visits to Sera, and failed to identify Ptolemy's Serica with the Cathaia of Marco Polo, as had been done before him by Fra Mauro, we are not able to rank him as high as a critical cartographer as he undoubtedly ranks as an astronomer. He may have been the initiator" of the voyage which resulted in the discovery of America, but cannot be credited with being the hypothetical" discoverer of this new world. That honour, if honour it be, in the absence of scientific arguments is due to Crates of Mallos, who died 145 years before Christ, whose Perioeci and Antipodes are assigned vast continents in the Western Hemisphere, or to Strabo (b. 66 B.C., died 24 A.D.), whose other habitable world" occupies the site of our North America.

Jean de Bourgogne, dit à la barbe, a learned physician of Liège, declared on his death-bed (in 1475) that his real name was Jean de Mandeville, but that having killed a nobleman he had been obliged to flee England, his native country, and live in concealment. This pretended Englishman is the author of a book of travels which W. D. Cooley(15) describes as "the most unblushing volume of lies that was ever offered to the world," but which, perhaps on that very ground, became one of the most popular books of the age, for as many as sixteen editions of it, in French, German, Italian and Latin, were printed between 1480 and 1492. In the original French the author is called Mandeville, in German translations Johannes or Hans von Montevilla, in the Latin and Italian Mandavilla. Behaim calls him Johann de Mandavilla, as in Italian, although six editions of his work printed in German, at Strassburg and Augsburg, were at his command. I conclude from this that he is indebted to an Italian map and not to a perusal of his `Travels' for the two references on the globe. The first of these (near Candyn) refers to the invisibility of the Lodestar in the Southern Hemisphere and the Antipodes, and is one of the four original statements of the learned doctor, and the second describes the dog-headed people of Nekuran (c. 18), which he has borrowed from Odoric of Portenone and enlarged upon.

Portolano charts were widely distributed in Behaim's time, and the fact that the Baltic Sea (Ptolemy's Mare Germanicum) appears on the globe as Das mer von alemãgna, instead of Das teutsche Mer, is proof conclusive that one of these popular charts was consulted when designing the globe or preparing the map which served for its prototype. Further evidence of such use is afforded by the outline given to the British Isles, and possibly also by a few place names in Western Africa, which are Italian rather than German or Portuguese.

![]() Catalan Map of the World, 1375

Catalan Map of the World, 1375

But whilst improving Ptolemy's northern Europe with the aid of a Portolano chart, he blindly followed the Greek cartographer in his delineation of the contours of the Mediterranean, and this notwithstanding the fact that the superiority of these Portolano charts had not only long since been recognised by all seamen who had them in daily use, but also by the compilers of a number of famous maps of the world, including the Catalan Map of 1375, which the King of Aragon presented to Charles V. of France, and whose author may have been Hasdai Cresques, a Jew of Barcelona;(17) a map of 1457, for which we are indebted to the learned Camadulite Fra Mauro, and another of the same date, elliptical in shape, whose unknown author, a Genoese, endeavoured to reconcile the conflicting views of orthodox cosmographers" and mariners of experience. Behaim, however, erred in good company, and for years after the completion of his globe the mistaken views of Ptolemy respecting the longitudinal extent of the Mediterranean were upheld by men of such authority as Waldseemüller (1507), Schöner (1520), Gerhard Mercator (1538), and Jacobus Gastaldo (1548). It is curious that not one of these learned "cosmographers" should have undertaken to produce a revised version of Ptolemy's map by retaining the latitudes (several of which were known to have been from actual observation), whilst rejecting his erroneous estimate of 500 stadia to a degree in favour of the 700 stadia resulting from the measurement of Eratosthenes (Strabo, II., c. 5). The result of such a revision is shown on this little sketch, the scale of which is the same as that of the Maplets on p. 36.

![]() The Mediterranean: Ptolemy amended

The Mediterranean: Ptolemy amended

The chart which the learned Toscanelli sent, in 1474, to his friend Fernão Martins has been lost, whilst the only information to be found in the letter which would enable us to reconstruct it are the statements that on sailing due west from Lisbon, Quinsay in Mangi would be reached after sailing across 26 "spaces" (of the projection) or 130 degrees of longitude, and that the distance between Antilia and Zipangu amounted to 50 degrees. The distances on Behaim's globe are approximately the same.(19) S. Ruge (`Columbus,' 1890, p. 62) concludes from this that Behaim may have copied Toscanelli's chart. This is quite possible, for copies of both the chart and the letter may have been forwarded by Toscanelli to his friend Regiomontanus at Nuremberg, who had dedicated to him, in 1463, his treatise `De quadratura circuli.'

When Behaim, in the spring of 1490, left Lisbon for his native Nuremberg, Bartolomeu Dias had been back from his famous voyage round the Cape for over a twelvemonth, numerous commercial and scientific expeditions had improved the rough surveys made by the first explorers along the Guinea coast, factories had been established at Arguim, S. Jorge da Mina, Benin and, far within the Sahara, at Wadan, trading expeditions had gone up the Senegal and Gambia, and relations established with Timbuktu, Melli and other states in the interior. In addition to all this, ever since the days of Prince Henry and the capture of Ceuta, in 1417, information on the interior had been collected on the spot or from natives who were brought to Lisbon to be converted to the Christian faith.(20)

There is no doubt that the early Portuguese navigators brought home excellent charts of their voyages. Columbus, who saw the charts prepared by Bartolomeu Dias, speaks of them as depicting and describing from league to league the track followed" by the explorer. But not one of these original charts has survived, and had it not been for copies made of them by ltalians and others, our knowledge of these early explorations would have been even less perfect than it actually is. These copies were made use of in the production of charts on a small scale, the place names upon which, owing either to the carelessness of the draughtsmen or their ignorance of Portuguese, are frequently mutilated to an extent rendering them quite unrecognisable. But even of maps of this imperfect kind illustrating the time of Behaim and of a date anterior to his globe, only two have reached us, namely the Ginea Portugalexe" ascribed to Cristofero Soligo, and a map of the world by Henricus Martellus Germanus.(21)

![]() The

World according to Fra Mauro, 1457

The

World according to Fra Mauro, 1457

![]() The World according to Henricus Martellus Germanus, 1489

The World according to Henricus Martellus Germanus, 1489

Behaim, of course, enjoyed many opportunities for examining the charts brought home by seamen not only, but also other curious maps, whose existence has been recorded although the maps themselves have long since disappeared. Among maps of this kind was one in the possession of D. Fernando, the son of King Manuel, in 1528, and which had been brought to the famous monastery of Alcobaça 120 years before, i.e., in 1408; another, which D. Pedro, the brother of Prince Henry, had brought from Venice in 1428, and upon which, according to Galvão,(22) was shown the "Fronteira de Africa" not only, but also a "Cola do dragon" or dragon's tail, which has been absurdly identified with the strait discovered by Magellan; the copy of Fra Mauro's famous map, for which King Affonso, in 1459, had paid 62 ducats; the map which had been prepared under the eyes of the learned Diogo Ortiz de Vilhegas of Calzadinha for the guidance of Pero de Covilhã in the east; the map of the world, fourteen palmas or about 10 feet in diameter, which H. Müntzer, in 1495, saw hanging on a wall of the royal mansion in which he resided as the guest of Joz d'Utra; and lastly, the map which Toscanelli is believed to have forwarded to King Affonso in 1474 in illustration of his plan of reaching China and Japan (Cipangu) by sailing across the Western Ocean.

In addition to maps and charts a person of Behaim's social position and connections might readily have had access to the reports of contemporary explorers. He might have learnt much from personal intercourse with seamen and merchants who had recently visited the newlydiscovered regions or were interested in them. His contemporary, the printer, Valentin Ferdinand, was thus enabled not only to consult the MS. Chronicle of Azurara,(23) and the records of Cadamosto(24) and Pedro de Cintra,(25) but also to gather much valuable information from Portuguese travellers who had visited Guinea. Foremost among these was João Rodriguez, who resided at Arguim from 1493-5, and there collected information on the Western Sahara. To Ferdinand we owe, moreover, the preservation of the account which Diogo Gomez gave to Martin Behaim of his voyages to Guinea.(26)

Having thus pointed out the materials available for the compilation of a map fairly exhibiting the results of Portuguese discoveries up to the time of Behaim, I shall next inquire into the extent to which these results have been considered in preparing the design for the globe. The readiest and most intelligible way to do this is to place, side by side, three maps of each group of islands, drawn on the same scale, the first according to Behaim, the second according to the "Ginea Portugalexe" of 1485, above referred to, or, in the case of the Canaries, by Andrea Benincasa (1476), and the third according to modern surveys. The result is shown on Map 4. The little maps there placed side by side prove two things, first, the surprising accuracy of the surveys made by Portuguese pilots, secondly, the utter incompetency of Behaim as a cartographer. Even the Azores, where he was at home, and concerning which we might suppose him to be well informed, are no more correctly delineated than the other island groups. Fayal, where he is supposed to have observed the stars (see p. 50) is placed by him in lat. 42° N., and at a distance of 2,000 sea-miles from Lisbon, when its true latitude is 38° 40' N., and the distance less than 900 miles. The chain, which extends for 400 miles towards the W.N.W., is given an extension of 960 miles. In like manner the Canaries stretch through 850 miles instead of 280, whilst the Cape Verde Islands are placed 660 miles to the west of the Cape after which they are named, when the actual distance is only 330 miles.

In order to enable the reader to judge readily of the extent to which Behaim has availed himself of the knowledge acquired by the Portuguese concerning the interior of Africa, I have compiled, from readily available contemporary sources, a map designed to illustrate the question (Map 5). The coast-line from Lisbon as far as Montenegro, where Cão set up his second pillar in 1482, is an exact reduction of the map of "Ginea Portugalexe" referred to on p. 26. No parallels are shown on the original. I have therefore assumed Lisbon to lie in 39° N., and a degree to be equal to 75 milhas (see p. 26), and marked the degree in the margin on the right side. The coast to the south of Montenegro, as far as Dias' furthest, I might have copied from the rough map of Henricus Martellus, but I felt justified to avail myself of the chart of Juan de la Cosa. This map, although dated 1500, and consequently drawn after the return of Vasco da Gama from India, in spite of its ample but fanciful nomenclature along the east coast of Africa, does not yet embody the results of that voyage. Even the landfall of Vasco da Gama, the Bay of St. Helena, is not shown upon it.

The information on inner Guinea available for my purpose is not very ample, but its utilisation by a competent cartographer would have much improved the map of that part of Africa. Azurara had already learnt a good deal about the inhabitants of the Western Sahara, among whom his informant, João Fernandez, had spent a couple of years (1445-7), but Cá da Mosto is the earliest traveller who furnished information of a nature sufficiently precise to be laid down upon a map. From Arguin, the Portuguese factory on the coast, he reckons six days' journey for camels to Oden (Waden), and six days more to Tegazza, whence rock salt is exported to Tombuto, a journey of forty days on horseback. From Tombuto to Melli he reckons thirty days. Melli exports gold to Cochia,(27) on the road to Cairo; to Tunes, by way of Tombuto and Tuet; and to Oran, Morocco, Fessa (Fez), and Mezza by way of Oden. It appears thus that he supposed Melli to lie to the west or south-west of Tombuto. More important is the information communicated by Diogo Gomez to Martin Behaim. According to him the road from Adem (Waden) to Tambucutu crosses the Abofar Mountains, which extend as far as Gelu (Jalo), south of Cantor on the Gambia, and separate the rivers flowing west, such as the Senega and Gambia, from those flowing to the east. He also describes a route leading from Cantor eastward through Çerekule(28) to Quioquia, the residence of Ber Bormelli, on a River Emin, which exports gold to Cairo, Tunes and Fez. A lake is near it. Caravans going from Tunes to Tambucutu cross a sea of sand-Mar arenosa-during 37 days. The Moses(29) of my map are inserted to the east of Tombutu, on the authority of Bemoyn, King of the Jalof, who was at Lisbon in 1488; King Ogane, according to J. A. d'Aveiro (1485). This prince, the King thought, might turn out to be Prester John. The remaining names on the map are taken from A. Benincasa's map of the Mediterranean.

If now we turn to the globe we shall find that not any of the above information has been utilised by its author. There is a king Mormelli and a king Organ, but the sites assigned to them are evidently from some other source. Neither Odan (Wadan), Tombuto, nor Cantor on the Gambia, are indicated, and yet they were places of interest in the Portugal of Behaim's time. The valuable information given by Gomez respecting the divide between the rivers flowing west and east is absolutely ignored.

Foremost amongst these rank the maps in the Ulm edition of Ptolemy (1482), of which Dominus Nicolaus, a German residing in Italy, was the author.(30) Of these maps that of Scandinavia is a curtailed version of one drawn in 1423 by Claudius Clavus Swartho (Niger), a Dane who lived at Rome. His map shows the actual Greenland as extending from Europe to beyond Iceland. On the map of Nicolaus published in 1482, though not in an earlier edition, Greenland is omitted.

Bartolomeo of Florence, who is said to have travelled for twenty-four years in the East (1401-1424), but whose name and reputation are otherwise unknown, is quoted at length on the spice trade.(31)

Behaim's laudable reticence as to "mirabilia mundi" has been referred to already (p. 59), but he does not disdain to introduce long accounts concerning the "Romance" of Alexander the Great, the myth of the "Three Wise Men" or kings, the legends connected with Christian Saints, such as St. Thomas, St. Matthew, St. Apollonius, and St. Brandan or St. Patrick, or the story of Prester John, all of which were popular during the Middle Ages. He quotes Genesis (instead of Kings ii. 13) in connection with Ophir, and refers to St. Jerome's introduction to the Bible.

If the reader will refer to the map illustrating the "Sources of Behaim's Globe," or to the Nomenclature" which follows, he will find that I have been unable to trace the origin of many features and names met with. I believe that if we were in possession of the materials at Behaim's command whilst he was at Nuremberg, we should find a solution for many questions which now puzzle us, not only with reference to this globe, but also in connection with many maps of the same period. At Nuremberg he was able to associate not only with men of travel, like his patron and fellow worker George Holzschuher, but also with others who took an interest in geographical work, such as Dr. Hieronymus Müntzer or Monetarius, Dr. Hartmann Schedel, and Bernhard Walther. From these he may have learnt all about the missions upon which Frederick III. sent Nicholas Poppel to Russia, in 1486 and 1488, for Poppel came to Nuremberg on the return from his first journey, and rendered an account of his mission to the assembled "Reichstag."(32)

Of H. Schedel we know that he took an interest if not an actual share in the making of the globe. We learn this from a memorandum in Schedel's hand discovered by Dr. R. Stauber(33) on a blank leaf of an edition of `Dionysius Ofer, De Situ orbis habitabilis' (1477), where he says :

"We produced (profecimus) this work from the most illustrious cosmographers and geographers of antiquity, such as Strabo, Pomponius Mela, Diodorus Siculus, Herodotus, Pliny Secundus, Dionysius and others, as also from moderns, including Paul of Venice (Marco Polo), Petrus de Eliaco (Pierre d'Ailly), and the very experienced men of the King of Portugal."

Further on he tells us, however, that the globe is absolutely the work of M. Behaim, and adds Ptolemy to the authorities claimed to have been consulted.

Behaim had access, likewise, to valuable collections of books and maps, most important among which was the library of the famous Johann Müller of Königsberg (Monteregio), who at the time of his death was engaged upon a revised edition of Ptolemy,(34) which he intended to illustrate with modern maps, including one of the entire world. The library had been purchased in 1476 by his friend and pupil, Bernhard Walther.(35) There are three sections of the globe, upon the origines of which much light might be thrown by the discovery of ancient maps formerly in the possession of John Müller. These are first the region between the Euphrates and Ganges; secondly south-eastern Asia with its many islands; thirdly the greater portion of inner Africa. As to the first it is remarkable that although Ptolemy's outlines of lakes and rivers have been retained, his place names have for the most part been rejected and others substituted, the source of which I have not been able to trace. Eastern Asia, with its islands, and Africa have, however, been copied from a map or maps which were also at the command of Waldseemüller. A comparison of that cartographer's map with Behaim's globe leaves no doubt as to this, unless we are prepared to assume that Waldseemüller took his information from the globe, which I have shown (p. 64) to be quite inadmissible. It was on the same map that Ritter von Harff,(36) who returned to Germany in 1499 after a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, performed his fictitious journey from the east coast of Africa, across the Mountains of the Moon and down the Nile to Egypt. On Behaim's globe may be traced twentyone names, out of about forty to be found on Waldseemüller's map of 1507, and four of them mark stages of the worthy knight's journey.

But long before Waldseemüller and Behaim, the same old map must have been accessible to Dom. Nicolaus Germanus, for in the map of the world in the edition of Ptolemy published in 1482 he introduces a third head stream of the Nile, which is evidently derived from it.(37)

Among maps not yet discovered are those reported to have been designed by two distinguished Italian artists, Ambrogio Lorenzetti of Siena (1290-1348) and Giovanni Bellini of Venice (1428-1516).

There is one other map to which I may refer. In the Nuremberg city library (Bibl. Solg. I., No. 34) there is a codex of 1488 containing accounts of the travels of Marco Polo, St. Brandan, Mandeville, Ulrich (Odorico) of Friaul, and Hans Schildberger, the original owner of which, Matthaus Bratzl, steward (Rentmeister) of the Elector of Bavaria, had a costly" map prepared to illustrate these travels. He desired that book and map should never be separated, but the map is no longer to be found.(38) Behaim's globe contains no data which can be traced to Odorico or Schildberger.

Behaim is no doubt indebted to his globe, and to the survival of that globe, for the great reputation which he enjoys among posterity. But whilst the undoubted beauties of that globe are due to the miniature painter Glockenthon, the purely geographical features do not exhibit Behaim as an expert cartographer, if judged by modern standards. He was not a careful compiler, who first of all plotted the routes of the travellers to whose accounts he had access, and then combined the results with judgment. Had he done this, the fact of India being a peninsula could not have escaped him; the west coast of Africa would have appeared as shown on Map 5. His delineation is rather "hotch-potch" made up without discrimination from maps which happened to fall in his hands. In this respect, however, he is not worse than are other cartographers of his period: Fra Mauro and Waldseemüller, Schöner and Gastaldo, and even the famous Mercator, if the latter be judged by his delineation of Eastern Asia.

But we may well ask whether greatness was not in a large measure thrust upon Behaim by injudicious panegyrists; and if, on a closer examination of his work, he does not quite come up to our expectations, they, at all events, must bear the greater part of the blame.

If, like the ghost of Hamlet's father, Behaim could have revisited the glimpses of the moon" and wandered through his native town when the German geographers met there in May, 1907, he may be supposed to have stared at the fine monument erected in his honour, beheld wonderingly a medal upon which his portrait was associated with that of Albert Dürer, and listened with a smile to the "Festspiel," "Im Hause Martin Behaims," written by Frau Helene von Forster.

(1) Letters and figures within brackets refer to the gores and latitudes of my facsimile, viz., (A 20) stands for gore A, lat. 20°. back

(2) Isidor of Seville was born about 560 and died Bishop of Seville in 624. He is the author of an encyclopædic work, `Originum sive etymologiarum libri XX.,' which enjoyed much authority during the Middle Ages. This work contains a `Liber monstrorum' (see K. Miller, `Die ältesten Weltkarten,' VI., Stuttgart, 1898). back

(3) Vincent of Beauvais, a learned Dominican, and tutor of Prince Philip, the son of Louis IX., was born before 1194. He died in 1264. back

(4) Marco Polo was born 1250. He left Venice with his father and uncle in 1271. The three travellers returned to Venice in 1295. Marco Pole dictated a narrative of his travels whilst a prisoner of war at Genoa. He died in 1324. back

(5) `Hie hebt sich an das puch des edeln Ritters vn landtfarers Marcho Polo,' Nuremberg (F. Creuszner), 1477. back

(6) `Incipit prologus in Libro domini marci pauli,' Antwerp (G. de Leeu), 1485. A 3rd edition of Yule's `Marco Polo,' by H. Cordier, appeared in 1903. back

(7) Giambattista Ramusio, the learned editor of these `Navigationi,' was born in 1486 and died in 1557. He was engaged upon his great work from 1523 to his death, but only its first volume was published in his lifetime. back

(8) And even the world maps of such distinguished geographers as Petrus Apianus (1540) and Simon Grynaeus (1532). Schöner was content to copy Waldseemüller's map of 1507. back

(9) This duplicated India includes, in fact, India proper, the Malay peninsula (Aurea chersonesus or Chryse) and Indo-China. back

(10) Placido Zurla, `Sulle antiche mappe idro-geografiche,' Venice, 1818. See inset on Map 3. Cardinal Placido Zurla of the order of Camaldulense, and an esteemed writer on the history of maps, was born at Legnaga 1759, died 18 . back

(11) See inset, Map 2. back

(12) H. Wagner, `Die Rekonstruktion der Toscanelli-Karte' (`Nachr. der K. Ges. der Wissenschaften,' Göttingen, 1894). Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli, the great astronomer and physicist, was born 1397 and died in 1482 (Uzielli, `Raccolta Colombiana,' Part V., vol. I., Rome, 1894). See also H. Vignaud, `The letter and chart of Toscanelli' (London, 1902), and his critics, H. Wagner (`Gött. gel. Anz.' 1902), L. Gallois (`An. de Géogr.,' 1902) and S. Ruge (`Zeitsch. f. Erdk.,' 1902). back

(13) Longitudinal Extent of the Old World. In comparing the meridional differences on non-graduated maps, the major axis of the Mediterranean has been assumed to measure 3,000 Portolano miles, equal in lat. 36 degrees to 3,690,000 m. or 41°. But if a degree of the Equator be assumed to contain 66 2/3 Roman miles of 1,480 m., then 11 per cent. must be added to the figures given for Nos. 3-7.

(14) For an excellent paper on Mandeville and the sources of his `Travels,' by Dr. A. Bovenschen (b. 1864 at Ostrowo), see `Zeitsch. f. Erdkunde,' XXIII., 1888, pp. 177-306. back

(15) `The History of Maritime and Inland Discovery,' I., p. 329 (London, 1830). back

(16) A description suggested by F. von Wieser, as describing without prejudice" the charts illustrating the Italian `Portolani' or sailing directories, previously known as Compass or Loxodromic charts. back

(17) Hamy, `Études,' p. 668. back

(18) See p. 64 for literary references. back

(19) Lisbon to Zeitun 126°, but to Quinsay 130°. back

(20) Such as Bemohi, King of the Jolof, and Caçuto of Congo. back

(21) For a notice of these maps see pp. 26, 67. The only original Portuguese chart of the fifteenth century discovered by Santarem is dated 1444, is on a small scale, extends no further than the Rio do ouro, and was not deemed worthy a place in his famous atlas. (See `Recherches,' p. 292.) back

(22) Galvão, `Tratado' (Lisbon, 1562), p. 67 of the Hakluyt Society's reprint, Antonio Ribeiro dos Santos, `Memoria sobre dois antigos mappas geographicos' (`Memorias de Litteratura Portugueza,' VIII., Seg. ed. Lisbon, 1856, p. 275). back

(23) Gomes Eannes d'Azurara, the author of the `Chronica do descobrimento e conquista de Guiné,' only published in 1841, and of other historical works, died about 1474. He had been appointed Keeper of the R. Archives (Guarda mór da Torre do Tombo) in 1454. back

(24) Luigi Cá da Mosto, a Venetian merchant, was born about 1432. He is generally credited with the discovery of the Cape Verde Islands. back

(25) An account of his Guinea voyage has been preserved to us by Cá da Mosto. back

(26) See p. 2. back

(27) The ruins of Kukiya (Cochia, Quiquia) were discovered by Lieut. Desplagne 95 miles to the south of Goa, on the right bank of the Niger (Rev. col., 1904, Sept.). back

(28) The Serekhule, on the south bank of the Senegal above the rapids. back

(29) Barros, `Da Asia,' Dec. I., liv. 3, c. 7; Ruy de Pina, c. 37. back

(30) Of these maps there are three sets or versions in MS. The first set was bought by the Duke Borso d'Este, about 1464; the second set (with three modern maps) was dedicated to Pope Paul II. (1464-71); a third version with five modern maps is now the property of Prince Waldburg. These last are the maps published at Ulm in 1482. back

(31) G. Uzielli, `Vita e i tempi di Toscanelli,' Raccolto Col., V., identifies this Bartolomeo of Florence with Nicolò di Conti, whom Enea Silvio (Pius II.) describes as a Venetian! See also W. Sensburg, `Poggio Braciolini und Nicolò di Conti' (Mittlen. Vienna g. Soc., 1906). Nicolò travelled 1415-40, Bartolomeo 1401-29! back

(32) Hormayr's `Archiv für Geographie,' etc., Vienna, 1829, No. 47. back

(33) R. Stauber, `Die Schedel'sche Bibliothek' (Freiburg, 1908), p. 60, a commentary by Dr. H. Grauert, ib., p. 257. About one half of Schedel's memorandum is borrowed, without acknowledgment, from the `Historia rerum' of Pope Pius II., especially lamentation on the want of appreciation of honest work. Does this refer to critics in Behaim's native town? (See Appendix VIII.) back

(34) A broadsheet printed at Nuremberg in 1476 enumerates the work which J. Müller proposed to carry out (Brit. Museum, IC. 7081). Joh. Werner, in 1514, published the first book of Ptolemy, which had been completed by him. Wilibald Pirckheimer embodied Müller's annotations in the Strassburg edition of 1522. back

(35) Walther by his last will and testament enjoined his heirs to part with this valuable collection of books and MSS. only as a whole, but they discarded this injunction, and in 1522 only 145 volumes were left. They were purchased for the town library, but hardly a dozen volumes are to be found in it to-day. (H. Petz, `Mitth. d. Ver. f. d. Gesch. d. Stadt Nürnberg,' VII., 1888, p. 217.) back

(36) `Die Pilgerfahrt des Ritters Arnold von Harff in den Jahren 1496-99;' `Nach den ältesten Handschriften,' von Dr. E. von Groote, Cöln, 1860. back

(37) See the insets on Map 2. Also my remarks on Wieser and Fischer's publication of Waldseemüller's maps, `Athenæum,' March 26, 1906, and `Geogr. Zeitschrift,' XII., Heft 3, 1906. There is reason to believe that a map discovered recently by Rev. Jos. Fischer, S.J., but not yet published, is one of the "lost" maps to which I have referred (`Stimmen aus Laach,' 1906, p. 353). back

(38) The Marco Polo of this codex is the edition printed at Augsburg in 1481; the other accounts are MSS. of the fifteenth century. back

Back to Table of Contents

Last modified: Tue Nov 7 00:03:24 CET 2006