Back to Table of Contents

THE discoverers of the Azores are not known to history. They may have been Vikings or Crusaders coming from the north on their way to the Mediterranean; Catalans, Genoese or Venetians driven out of their course whilst making for Flanders, England or Ireland. They certainly were not Portuguese. Prince Henry seems first to have seen these islands upon a chart which his far-travelled brother, D. Pedro, brought from Venice in 1428.(2)

This, however, is not the oldest available chart upon which the Western Islands are delineated, for they may already be seen upon one designed by a Genoese, in 1351, which is preserved in the Biblioteca Laurenziana at Florence.(3)

Even more ancient is a list of the islands in the account of an imaginary journey through all parts of the world which was compiled by a Spanish friar before the middle of the fourteenth century, which he entitled `Libro del conocimiento de todos los Reinos y Señorios.'(4)

Prince Henry, in 1431, despatched Gonçalo Velho Cabral(5) in search of these lost islands. Velho in that year discovered the Formigos or "ants," a group of low rocks lying between the islands of S. Maria and S. Miguel, either of which must have been distinctly visible from these rocks.

The second group of the Archipelago, including five islands, may have been discovered by Diogo de Sevilla, pilot of the King of Portugal, in 1437. Such at least is the statement in a beautiful map of the world by Gabriel de Valsequa, a Majorcan cartographer.(6) This map is dated 1439, and in that very year the youthful King Affonso V., with the consent of the Queen-mother and of the Regent D. Pedro, authorised his uncle Henry the Navigator to people the "seven islands of the Azores,"(7) thus named after the flocks of wild birds, supposed to be hawks (açores), but which were in reality kites (milhanos).

The third group, including Flores and Corvo, was certainly re-discovered before 1453, for in January of that year Corvo was granted to D. Affonso, Duke of Bragança, the bastard son of John I.(8) It is probable that the discoverer was João de Teive of Madeira, whose pilot, Pedro de Velasco, told Columbus at Rabide that this discovery had been made in 1452 in the course of an unsuccessful search after Antillia.(9)

On the death of Henry the Navigator, in 1460, the Azores were transferred to Don Fernando,(10) the Navigator's nephew and adopted son, and his successor as Master of the Order of Christ.(11) When Fernando died in 1470, he was succeeded by his son, Don Diogo, Duke of Vizeu, after whose murder by John II. in 1484, the islands were granted to the King's brother-in-law, Don Manuel, Duke of Beja, who subsequently became famous as King Manuel the Fortunate.

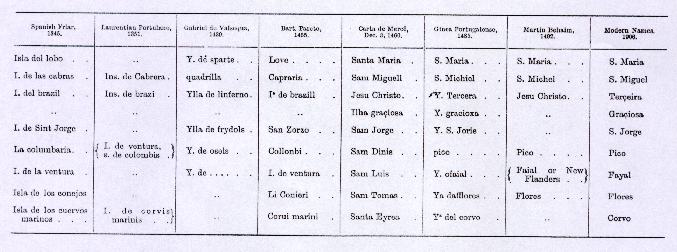

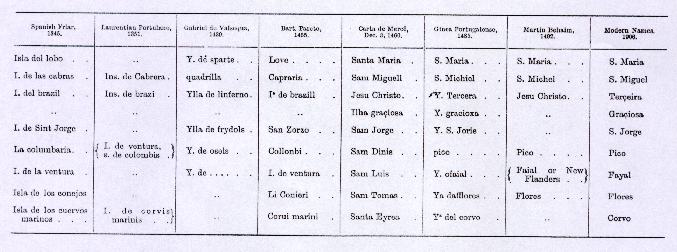

The names borne by the seven islands of the Azores, and of Corvo and Flores, since 1345 may be gathered from the table on page 47.

The nomenclature of the Spanish Friar is undoubtedly Spanish (and not Italian or Portuguese), and his knowledge of the archipelago was certainly more complete than was that of the Genoese compiler of the Laurentian Portolano Chart. The only island omitted by him is the Ilha graçiosa, which only made its appearance after the rediscovery of the archipelago had been inaugurated by Henry the Navigator. The Isla del brazil may owe its name to a dye-plant-orchil-which reminded its discoverers of the East Indian brazil, a dye wood which had found its way into Italy and Catalonia as early as the twelfth century. Isla del lobo, Seal Island, seems to me more appropriate than Lovo, the egg-shaped island, for S. Maria, resembles by no means an egg; originally S. Maria was named after its discoverer, Gonçalo Velho. The names of the other islands may be translated thus:-Goat Island, St. George, the Pigeon-cote, Venture Island, Coney and Cormorant Islands.

Santa Eyria (Iria) is called Santa Anna by Soligo (about 1480); whilst Faial on the map of modern Spain in the edition of Ptolemy published at Ulm in 1482 is called St. André.

The names on Gabriel de Valsequa's map are probably those given by Diogo de Sevilla.

The earliest settlers of the Azores were Portuguese and their "captivos," that is, Moors and negroes kidnapped on the coast of Africa. But Portugal was a small country, the resources of which, in men and treasure, had been wasted in unprofitable wars in Africa. The population remained stationary, if it did not decrease, and the country, which almost down to the close of the fourteenth century had exported wheat, had become dependent for part of its food supplies upon Flanders and Brabant.(12) These commercial relations with Lower Germany date back to the twelfth century, when Crusaders(13) from Flanders and the Lower Rhine helped the Portuguese in their struggles with the Moors. The Portuguese ever since 1385 had their "borsa" (factory or inn) at Brügge. The relations between the two countries became even closer when D. Isabel, the daughter of King John I., married Philip the Good of Burgundy, (14) in 1429. Many Flemings had settled in Portugal, and it is only natural that among those who solicited privileges in the newly discovered countries there should be compatriots of theirs.

Most prominent among the Flemings connected with the peopling of the Azores were Jacob of Brügge, Willem van der Haghe and Josse van Hurter.

Jacob of Brügge-Jacomo de Bruges-had been granted the captaincy of Jesu Christo or the ilha Terçeira on March 3, 1450. His experiences were disappointing, and when he died D. Brites, the widow of D. Fernando, Duke of Vizeu, in 1474, transferred the captaincy to João Vaz Cortereal,(15) the father of Gaspar, one of the earliest visitors, if not the discoverer, of Newfoundland, and Alvaro Martins Homen,(16) the one settling at the Angra, the other at a villa da Praia. Another Fleming, Fernão Dulmo or Ferd. van Olm, a cavalier of the Royal Household, is mentioned as one of the captains of Terçeira, who had established himself on the north coast of that island, at the Riveiro dos Flamengos. It was he who in 1486 jointly with João Affonso do Estreito proposed to fit out an expedition for the discovery of the island of the Sette cidades.(17)

Willem van der Haghe, whose name the Portuguese perverted into Vandaraga, whilst he himself had translated it as Guilherme da Silveira, first settled on S. Jorge, and having vainly tried his fortune in other islands, including Corvo and Flores, where he appeared as the representative of D. Maria de Vilhena,(18) returned in the end to S. Jorge, and became the founder of one of the wealthiest families in the Azores. His son, Francisco, married Isabel de Macedo, a daughter of Joz d'Utra; his grandson called himself Joz d'Utra da Silveira.(19)

Of far more interest is the history of Josse van Hurter,(20) for it was a daughter of this Captain donatory of Fayal whom Martin Behaim married about the year 1487.

The Hurters or Huertere were an old Flemish family, and as far back as 1336 they are mentioned as magistrates (échevins) of the liberty (Vrije) of Brügge. Their arms in 1354(21) were charged with three roundels, within each of which was depicted a star of six rays. The Hurters of Fayal, however, were not content with this simple coat of arms, but devised one more elaborate, as follows:

Shield, azul charged with three roundels or (i.e. bezants), each roundel charged with a cat sable. Crest: a vulture proper, armed or.(22)

Josse van Hurter, the first Captain donatory of Fayal and Pico, was the youngest son of Leo de Hurter, bailiff of Wynendaal and lord of Haegebrock, two dependencies of the village of Hooghlede, three miles to the N.W. of Roulers (Rousselaere) in Flanders. Behaim speaks of his father-in-law as Lord of Moerkerke, but the town clerk of that flourishing manufacturing town informs me that the name of Hurter is absolutely unknown there, and that the castle never belonged to a family of that name.(23)

After the death of Barthelemy, the eldest of the five brothers, who died a bachelor, Haegebrock became the property of his brother Baudouin or Baldwin, who seems to have kept up some intercourse with his relations in Fayal. There is still extant a letter which Diogo, a son of this Baudouin, wrote to Joz d'Utra in 1527.(24)

The circumstances under which Joz d'Utra became Captain donatory of Fayal(25) and Pico, notwithstanding the legends on Behaim's globe and the information furnished by Valentin Ferdinand,(26) are only imperfectly known.

We gather from these and a few other sources that D. Beatriz, the consort of D. Fernando, who had been granted the Azores after the death of Prince Henry the Navigator in 1460, had a chaplain, a Fleming named D. Pedro, whom she desired to reward for faithful service. This chaplain, in 1465, came to Flanders on a mission to D. Isabella, the consort of Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy. At the ducal court he became acquainted with Josse van Hurter, an equerry of the Duchess. This young nobleman had three wealthy brothers, but, having been attached to the court, his own estate had much suffered. When the friar spoke to him about the Azores, and their supposed wealth in silver and tin, young Hurter saw rising before him a vision of great wealth. When the friar promised to use his influence, and to obtain for him the captaincy of one of these islands, he eagerly embraced the offer.

Having secured at Brügge the co-operation of fifteen competent workmen (trabalhadores), whose fortunes he promised to make, he went to Portugal. Thanks to the recommendations of the chaplain, backed, as they probably were, by the Duchess Isabella of Burgundy, he obtained leave to people Fayal.(27)

He took his fifteen companions to that island, and no doubt a number of other colonists, but the venture ended in disappointment. Neither silver nor tin was found, and when the colonists, after a year's search, had come to the end of their resources they turned upon their leader, and threatened him with death.(28) Hurter escaped their violence and returned to Portugal. D. Fernando and his consort admired his spirit of enterprise. They not only promoted his marriage with Brites (Beatriz) de Macedo, a beautiful maid of honour in their household,(29) but also furnished him with ships and men, which enabled him to return to Fayal. Having re-established his authority, the colonists introduced by him set to work; they grubbed up the soil; cattle were imported from the neighbouring islands, and in the course of time Willem Bersmacher, a Fleming, introduced the cultivation of woad, which proved profitable. The island, however, does not appear to have proved a source of wealth to its captain donatory. It yielded orchilla, woad, wheat, oranges, and lemons and a little wine, and afforded forage for cattle and pigs, but ready money seems at all times to have been scarce. Brites de Macedo, the wife of Joz d'Utra, in her will of 1527,(30) refers to a debt of thirty years' standing, whilst Dr. Monetarius, (31) writing in 1494, tells us "vectigalia apud ipsos sunt in bono foro, sed divitiae argentae non magnae," which I take to mean that though victuals were plentiful there was always a lack of ready money.

The captães donatorios or hereditary governor of the islands discovered by the Portuguese were appointed either by the king himself or by the person to whom the island had been granted. The dignity was hereditary, as a rule, in the male line only. In the case of the death of a grantee his lawful successor was bound (in conformity with a law of 1434) to apply to the king for a confirmation of the act by which his family originally benefited, and this confirmation might be refused. Such application was usual also on the accession of a sovereign.

The captain was entrusted with the exercise of criminal and civil jurisdiction, subject to respecting Royal writs and the decision of judges in circuit (correiçaos), and to the limitation that sentences, involving the loss of a limb or death, had to be referred to the king for confirmation. He enjoyed the monopoly in corn-mills, public baking houses and the sale of salt, and was entitled to claim the payment annually of one mark silver (or of two deals a week) from the owner of a saw mill, and a tenth of the profits of all metalliferous mines. The captain, moreover, was authorized to grant land to colonists on payment of a rent in money or in kind, and on condition that it was brought under cultivation within five years. Land not cultivated might be claimed by the king. Tenants, however, were permitted to sell the tenant rights of the land they had brought under cultivation, to kill wild beasts and to pasture their tame cattle throughout the island. The governor moreover enjoyed the tenth of the Royal revenues. His privileges were consequently very considerable, and abuses of the powers entrusted to him were by no means rare.

Martin Behaim most certainly exaggerates when he tells us that the Duchess of Burgundy sent 2,000 colonists to the island, which increased so rapidly that in 1490 there lived there many thousand Germans and Flemings; for Monetarius, who was at Lisbon in 1494,(33) was told by the wife of Joz d'Utra that at that time, and including Pico, there were only 1,500 inhabitants of both sexes, all of them Flemings. But whatever the original number of Flemish colonists, they quickly became merged with or were superseded by the Portuguese. As early as 1507, we are told by Valentin Ferdinand, the Flemish language was nearly extinct, and when Jan Huyghen van Linschoten(34) resided in the Azores (1589-91) the Flemish language had become extinct, although many of the inhabitants resembled Netherlanders in physique, and thought kindly of their forefathers.

It is owing to the early Flemish settlers that the islands of Fayal and Pico became known as the "<81>Flemish islands." Abraham Ortelius, the eminent geographer (born 1527 at Antwerp, died 1598), in the notes accompanying Ludovicus Teisera's map of the <81>"Açores Insulae, 1584," extends this appellation-Vlaemsche eylanden-to the whole group, on the ground that merchants of Brügge had been the first to discover them.

Josse van Hurter, the first Captain donatory of Fayal, as has been already stated, married D. Brites or Beatriz de Macedo, a maid of honour in D. Fernando's household, and a member of one of the most illustrious families of Portugal. Her ancester, Martin Gonçalves de Macedo, had saved the life of King John I. at the battle of Aljubarrota, 1385.(35) Her family owned estates in Madeira, and these yielded the sugar which her husband exported to Flanders.

There were six children by this marriage. The eldest son, named like his father, Joz d'Utra, married Isabel, the daughter of João Vaz Cortereal; a daughter, Isabel,(36) married Francisco da Silveira (v. d. Haghe); another daughter, Joanna, married Martin Behaim.

The captain donatory and, at all events, his family appear to have spent much of their time at Lisbon. It was there that Dr. Monetarius, when he stayed in that city from November 27 to December 2, 1494, was hospitably entertained by the family of Joz d'Utra. They occupied one of the King's houses in the Rocio, near the church of S. Domingos. Dr. Monetarius(37) describes the lady of the house as being of "�noble birth, intelligent and of wide experience." She presented him with a sample of musk obtained from S. Thomé. Dr. Monetarius makes no reference whatever to his old friend Martin Behaim, who was probably at Fayal, nor to Valentin Ferdinand, who acted as his interpreter.

Joz d'Utra died in 1495,(38) and was succeeded by his eldest son, who bore the same name. An incident in the life of this governor is of some interest to us, as an official document connected with it refers to the wife of one Martin Behaim.(39)

It appears that Joz d'Utra charged Fernão d'Evora, who had been appointed in July, 1492, Mamposteiro mór dos Captivos(40) for the Azores, with having been found with his sister Joanna, the wife of Martin Behaim. The accused was put in chains and embarked for Lisbon, but managed to escape. The King on November 16,1501, granted him a "carta de perdão" (pardon), but when he returned to the Azores, he was once more cast into prison. In the end his son succeeded in proving his innocence of the adultery charged against him, and Joz d'Utra was ordered to molest him no further.

Manuel d'Utra Cortereal, the son of Joz d'Utra II. and his wife Izabel Cortereal, succeeded in 1549, but being charged with bigamy he was removed from his high position, and it was only after a protracted law-suit(41) that his son and heir, Jeronimo d'Utra Cortereal, was given possession of his father's office. This happened in 1582. Jeronimo departed this life in 1614, the last of his line, his only son Luiz having died before him in India, in 1600. After his death the captaincy of Fayal and Pico was granted to D. Manuel de Moura Cortereal, the first conde de Lumiares.(42)

Of Martin Behaim's family life in Fayal we know next to nothing. We are unacquainted even with the circumstances which led to his marriage with Joanna de Macedo, the daughter of Joz d'Utra. This marriage took place at latest in the spring of 1488, for his son Martin was born April 6, 1489.(43) There were no other children. Such at least is the result of careful inquiries made in 1518 by Jorg Pock by request of the family.(44) E. do Canto (`Arch. dos Açores,' VII., pp. 401-415) declares that he had no further descendants in the male line.

After the death of her husband, in 1507, the widow, <81>"being at the time still young, and it being the custom for young widows to marry again,"(45) wedded D. Henrique de Noronha of Madeira, and thenceforth resided in that island.

We do not know how Behaim was occupied after his return from his African voyage, during his residence at Fayal or during occasional visits to Lisbon. It is to be presumed that he assisted his father-in-law in the management of his estate. He may even have dabbled in astrology, and devoted some time to the study of cosmography, but there is no evidence whatever that he followed a maritime career. The only voyage of discovery with which his name has been associated is a joint expedition proposed by Fernão Dulmo (Ferd. van 0lm), one of the captains of Terçeira and João Affonso do Estreito of Madeira, which was authorised by King John on July 24, 1486. Two caravels were to leave Terçeira in March 1487, in search of the mythical "<81>Ilhas das sete cidades," and of a <81>"terra firme," and it was agreed that the "<81>German cavalier who desired to join this enterprise should be permitted to embark in either of the caravels." Ernesto do Canto suggests that this "German cavalier" can have been no other than Martin Behaim. But if this is the case, and if the expedition really started, it is curious that no reference to it whatever should be discoverable on Behaim's globe.(46)

It might be supposed that valuable and trustworthy information on Martin Behaim might be found in the `Historia insulana das ilhas a Portugal sujeitas na Occano occidentale,' compiled by Antonio Cordeira, and published at Lisbon in 1717, for the author was able to avail himself of a valuable MS., `As saudades da terra,' compiled by Dr. Gaspar Fructuoso.(47) His work unfortunately contains but little information. He tells us (IX., c. 3, § 41):

"Martin de Bohemia was a great mathematician and so distinguished an astrologer that the King, when he came to the Court, esteemed him highly, not only on account of his noble birth, but also on account of his learning, and the knowledge which he owed to the observation of the stars. This was so remarkable that the King, trusting to this knowledge, despatched vessels for the discovery of the Antilhas (West Indies), and Bohemia foretold day and hour when these vessels would return, and they did return without having discovered the Antilhas. And he divined so many other things by observing the stars, and these things turned out afterwards to be true, that the ignorant people, instead of looking upon this nobleman as an excellent astrologer, took him to be a necromancer."

This prophecy may refer to any of the expeditions which sailed to the west, and not one of them met with success. Fructuoso after this communicates three prophecies of a more remarkable nature, all of which, he maintains, turned out true. They are as follows:

"In the first place he (Behaim) said that a time would come when a man would be happy who had a good ship, which would enable him to leave these islands. And this was found to be true during the troubles and wars(48) between Philip of Spain and his cousin D. Antonio, in the time of the conflagrations (volcanic eruptions), earthquakes, etc.

"In the second place, and before the discovery of the Indies of Castile, he said that to the south-west of Fayal, where he then was, he saw a planet dominating a province the inhabitants of which used dishes of gold and silver, cargoes of which would reach Fayal before long. And within a few years vessels laden with gold, silver and precious stones coming from Peru arrived at Fayal.(49)

"In the third place he said that to the south-west of Fayal and Pico three islands remained to be discovered, one of which was very large and properly called Madeira, the other was smaller, and the third was the smallest."(50)

Dr. Günther (p. 70) suggests that Behaim's reputation as a prophet may have been due to his predicting eclipses of the sun or moon, which he might have done, without consulting the stars, by consulting a book like the `Calendarium ecclipsium p. a. 1483-1530,' in his days in common use among seamen.

(1) J. Mees, `Hist. de la découverte des îles Açores' (Ghent, 1901); P. J. Baudet, `Beschryving van de Azorische eilanden' (Antwerp, 1879). back

(2) D. Pedro, Duke of Coimbra, son of John I., was born in 1391. He was regent of the kingdom during the minority of his nephew, Affonso V., 1433-49, when he was killed at the battle of Alfarrobeira. His children fled to the Court of the Duke of Burgundy. On this chart see p. 40, note. back

(3) Facsimiles of this Portolano chart, also known as the `Medicean Portolano,' because included in a library founded by the Medici, have been published by Theob. Fischer and A. E. Nordenskiöld (`Periplus,' X.). back

(4) Marcos Jimenez de la Espada, who published this interesting document in the Boletin of the Geogr. Society of Madrid, II., 1877, believes the friar to have been born in 1305, and the `Conocimiento' to have been compiled in 1345. back

(5) Ayres de Sá, `Frei Gonsalo Velho,' 3 vols., Lisbon 1893-1900. Cabral was the family name of Velho's mother. See Plate for a map of these islands. back

(6) Hamy, `Études,' pp. 111-120, furnishes information on this cartographer, and publishes his chart of the Mediterranean drawn in 1449, and purchased by Amerigo Vespucci for 130 golden ducats. His map of the world has not yet been published. back

(7) `Alguns documentos,' p. 6.. back

(8) `Alguns documentos,' p. 14. back

(9) Harrisse, `Christopher Columbus' (Paris, 1884), I., 311. In 1474 Diogo de Teive, the son of the discoverer, was authorised to cede the island to Fernão Telles (`Alg. doc.,' p. 38). back

(10) D. Fernando, Duke of Vizeu, born 1433, was the son of King Duarte and the father of King Manuel and Queen Lianor, consort of King John II. His sister D. Leanor, married the Emperor Frederick III. in 1451. His widow, D. Brites or Beatrice, was a granddaughter of King Duarte. back

(11) Letters patent (carta de mercê) of December, 1460 (`Alg. doc.,' p. 27). back

(12) See an anon. `Memoria para a hist. de agric. em Portugal' (`Mem. de Litt. Port.,' II., 1792). back

(13) Flemish Crusaders, in 1147, took part in the siege of Lisbon; in 1189 they captured Silvas, and in 1214 Crusaders led by William I. of Holland and George von Wied took Alcaçer do Sal. back

(14) When Philip died in 1467, his widow retired to a convent and died there in 1469; Charles the Bold, their son, was born 1433, and fell at Nancy 1477. Their granddaughter Maria married Maximilian, King of the Romans, in 1477. back

(15) On this family see E. do Canto, `os Corte Reaes' (Ponta Delgado, 1883) and `Archivo dos Açores,' I., 155, 443; H. Harrisse, `Les Corte Real et leurs voyages,' Paris, 1883. João Vaz died 1496. back

(16) The letters patent are published in Drummond's `Annaes da ilha Terçeira,' 1800-1, and in the `Arch. des Açores,' IV., 159. back

(17) `Alguns documentos,' p. 58. back

(18) This lady, in 1473, was aia (governess) and Mistress of the Robes of D. Lianor, the sister of King Manuel and wife of John II. Her father was Martin Affonso de Mello, Governor of Olivença, her mother D. Margarita de Vilhena (A. Braancamp Freire, `Livro dos brasões,' I., 25; A. C. de Sousa, III., 142). back

(19) W. Guthrie (born 1708, died 1770), the reputed author of a "New System of modern Geography" (London, 1774), is responsible for the statement that the Azores were discovered by one Josuah van der Berghe in the middle of the fifteenth century. Baudet (l. c. pp. 97-103) fully discusses this question, and exposes the authors who spread the fable. back

(20) The Portuguese called him Joz d'Utra or de Hutra. Josse, Jobst, Jost and Jodocus are synonymus.. back

(21) `Registre de Franc,' 1354, No. 632, p. 92, kindly communicated to me by Dr. Mees. back

(22) I am indebted for this description to Senhor Gabriel Pereira. It is possible that the "cats" may be meant for "gatas de algalia" or civet-cats, and the vulture for a kite, this being the true representative bird of the Azores. back

(23) Nor is it correct to say that the Hurters originally came from Austria. There is a village Habrk in Bohemia, but Dr. Witting, the secretary of the Imp. Society of Heraldry "Adler," informs me that no Hurters are known in Austria. back

(24) `Archivo dos Açores,' I., 162. back

(25) Faial means beech-wood, but the beeches after which the island is named have turned out to be myrtles (Myrica Faya), just as the hawks (açores) have turned out to be kites. back

(26) See in Appendix XI., p. 114. back

(27) According to Valentin Ferdinand this happened in 1469; according to Behaim in 1466. back

(28) Cordeiro, `Hist. insulana,' VIII., c. 2, speaks of a revolt headed by Arnequim, a Fleming, who defied the Royal corregedor (magistrate), and threatened to shoot Hurter with his cross-bow. back

(29) Confirmed by Barros, `Chronica do Imperader Clarimundo,' Lisbon, 1601, t. I., liv. III., c. 1. back

(30) `Archivo dos Açores,' I., 164, 170. back

(31) `Abh. d. bist. Cl. d. K. bayr. Ak. d. W.,' VII., 1854, p. 361. back

(32) For conditions of a letters-patent (carta de mercê) of this kind see Mendo Trigoza, `Mem. da litt. Portuguese,' VIII., p. 390. back

(33) L. c., p. 361. back

(34) `Itinerarium ofte Schip-vaert n. e. Oost ofte Portugaels Indien,' (Amsterdam, 1644), pp. 146-157. back

(35) Arms of the Macedos as described by A. Braancamp Freire, `Livro dos brasões da sala de Cintra,' I., pp. 99, 113: field azure charged with five stars, or, in saltire. back

(36) This is the thona Isabel of George Pock. back

(37) For the account of Monetarius see `Abh. d. hist. Ch. d. K. bayr. Ak. d. W.,' II., 1847; VII., 1855. back

(38) His wife survived until 1531. For her last will and testament (1527) with a codicil (1531) see `Arch. dos Açores,' I., 164. back

(39) `Arch. dos Açores,' IX., 1887, p. 194. back

(40) Collector-in-chief of the captives or slaves. back

(41) See Cordeiro, `Hist. Insulana,' p. 458, for the history of the law-suit. back

(42) `Arch. dos Açores,' IV., 229. back

(43) This date is given in a letter of Michael Behaim to Jorg Pock dated December 16, 1518 (Ghillany, p. 43). back

(44) Ghillany, Urk. XVII. and XVIII. A. Cordeiro (`Hist. insulana,' VIII., c. 4), on the other hand, asserts that there were two sons both named Martin; that the father, after the death of the first-born, visited Bohemia, his native country, whence he came back with great wealth, but that after several years' residence he returned to Germany for good, and that neither he nor his second son were again heard of! back

(45) So says her son Martin in a letter of August 13, 1518, to Michael Behaim, his uncle (Ghillany, p. 108). The widow, in 1507, must have been close upon forty years of age, but she owned estates in Madeira! back

(46) Barnardino José de Senna Freitos, in his `Memoria hist. sobre o intentado descobrimento de uma supposta ilha ão norte de Terçeira,' (Lisbon, 1845), was the first to refer to this expedition. For the Royal authority see `Alguns documentos,' p. 58, and E. do Canto's `Arch. dos Açores,' IV., 441. Harrisse, `The Discovery of America,' p. 655, enumerates 13 expeditions which sailed between 1447 and 1493 in search of western islands. back

(47) For biographical notice on G. Fructuoso and A. Cordeira, see p. 3. Alvaro Rodriguez de Azevedo published an annotated edition of the `Saudades' as far as they refer to Madeira (Funchal, 1873). A work on Fayal by A. Pedro de Azevedo, I have been unable to obtain. back

(48) The war between Philip of Spain and D. Antonio, prior of Crato, broke out in 1580. The Azores, having declared in favour of D. Antonio, were invaded and conquered by the Spaniards in 1582-3 (Antonio de Herrera, `Cinco livros de la Historia de Portugal, y conquista de la islas de los Açores,' Madrid, 1591). A fearful earthquake occurred in 1522, and its ravages extended from the Azores to Morocco and Granada. back

(49) Peru was first heard of in 1524! back

(50) This of course may refer to Madeira, Porto Santo and Bugio. back

Back to Table of Contents

Last modified: Fri Feb 6 01:22:03 CET 2004