Back to Table of Contents

IT is to an alleged voyage with Diogo Cão, either as astronomer or, as he himself asserts, as captain of one of the two vessels of the expedition, that Behaim owes the title of Navarchus, Seefahrer, or Navigator. Behaim himself has given two versions of this voyage, but before placing these before the reader I shall sketch the progress of Portuguese discovery along the west coast of Africa up to the year 1490.(1)

When John II. in 1481 ascended the throne of his father Affonso, the Guinea coast had been explored as far as Cape S. Catherine. Lopo Gonçalves had been the first to cross the line; Fernão Pó is credited with having discovered in 1372 the Ilha formosa, which now bears his name; whilst Ruy de Sequeira "about the same time," according to Galvão,(2) followed the coast as far as Cabo de S. Catharina (November 25), and also discovered the islands of S. Thomé (December 21) and S. Antonio (January 17). The latter subsequently became known as Ilha do Principe, that is, the island of Prince John, the future King John II., who had enjoyed the revenues of the Guinea trade ever since 1473. This trade had become of importance, but nothing had been done to expand it since 1475, in which year the monopoly granted to Fernão Gomez came to an end, nor had steps been taken to render effective the claims to sovereignty put forth by Portugal. Hence foreign interlopers made their appearance upon the coast, and during the unfortunate wars with Castile (1475-80) entire fleets sailed from Spanish ports to share(3) in the profits of the trade there.

One of the first measures taken by King John was to put a stop to these irregularities. Royal ships were sent out to protect Portuguese interests, and on January 20, 1482, Diogo D'Azambuja laid the foundations of the famous Castella de S. Jorge da Mina, which was the first permanent European settlement on the Gold Coast, and the centre of Portuguese activity up to 1637, when it was captured by the Dutch.

King John, having thus attended to what he conceived to be his more immediate duty as a king and ruler, took up the long-neglected work of his uncle Henry the Navigator, for, as Ruy de Pina tells us, he was not only "a good Catholic, anxious for the propagation of the faith, but also a man of an inquiring mind, desirous of investigating the secrets of nature."(4)

The King appointed Diogo Cão to the command of the first expedition despatched from Portugal to take up the exploration of the African coast beyond the Cabo de S. Catharina. Cão left Lisbon about June 1482, called at S. Jorge da Mina for supplies, and then followed the coast until a body of fresh water, five leagues out at sea, revealed the existence of a mighty river (rio poderoso) which had poured it forth. This river was the Congo. He there entered into friendly relations with the natives, and having despatched messengers with gifts to the king of the country, and set up a stone pillar at the river's mouth, he continued his voyage to the south. When he reached the Cabo do lobo, in 13° 26' S., now known as Cape St. Mary, he erected his second pillar or padrão.(5) This pillar, fortunately, has been recovered intact. An inscription upon it, in Portuguese, tells us that in the year 6681 of the world or in that of 1482 since the birth of Christ the King ordered this land to be discovered by his esquire (escudeiro) Diogo Cão. The coat of arms is that in use up to 1485, when King John ordered the green cross of the order of Aviz to be removed from it, the number of castles to be reduced to seven, and the position of the "quinas," or five escutcheons, to be changed.(6)

When Cão came back to the Congo he was annoyed to find that his messengers had not yet returned, and being naturally anxious to hasten home with a report of his important discovery, he seized four native visitors to his ship as hostages. He gave their friends to understand that they should be brought back in the course of time to be exchanged for his own men who were still with the king.

Cão came back to Lisbon in the beginning of 1484, and certainly before April of that year, for on the 8th of that month he was granted an annuity "in consideration of his services," and a few days afterwards was given a coat of arms charged with the two padrões he had erected on the coast of Africa.

Cão's departure on his second expedition was delayed until the latter part of 1485, and the padrões which he took with him were ornamented with the new coat of arms, recently adopted and dated 1485 A.D. and 6185 of the creation, the latter year beginning with September 1, 1485.(7) It seems that Cão, on this occasion, commanded three vessels, his fellow captains being Pero Annes and Pero da Costa. It is possible that Cão, when crossing the Gulf of Guinea, discovered the island called I. Martini on Behaim's Globe, and now known as Anno bom. Such a discovery is suggested by a rough map of an `Ilha Diogo Cam' depicted upon a loose sheet in Valentin Ferdinand's MS. The shape of this island, however, resembles in no respect the two delineations of the island of Anna bom given in the same MS., and no reference to it is made in the text.

Cão on reaching the Congo ascended it for about ninety miles, as far as the River Mposo, above Matadi, and within sight of the Yelala Falls, for there, upon some rocks upon the right bank an inscription(8) has been discovered which records this achievement. The coat of arms proves that this inscription dates from 1485, or a subsequent year. We there read: "Thus far came the vessels of the illustrious King D. João II. of Portugal: D° Cão, P° Annes, P° da Costa"; further to the right, "Alv° Pyrez, P° Escolar"; lower down, J° de Santyago, + of illness (da doença), J° Alvez (Alvares), + D° Pinero, G° Alvez-Antão." Still further away there is another cross with a few names-Ruys, Farubo, Annes, and a masonic symbol (X).

Several of the names given are those of well-known Portuguese seamen. A Pero Annes served under Albuquerque in India; Pero Escolar accompanied the Congo embassy in 1490-1, was pilot of one of Vasco da Gama's vessels, and accompanied Cabral to India; João de Santiago commanded the store vessel of the expedition of B. Dias.

The remaining names may have been cut into the rock subsequently to Cão's expedition of 1485. The name of Martin de Bohemia is looked for in vain. Cão, having landed the hostages whom he had carried off two years before, proceeded to the south. He kidnapped several natives, who were to be taught Portuguese so that they might serve as interpreters in future expeditions. On the face of `Monte negro,' 15° 41' S., he erected a padrão, and a second at Cape Cross, described as Cabo do padrão and Sierra parda on old maps, in 21° 50'. The former of these pillars is now in the Museum of the Lisbon Geographical Society, its inscription quite illegible; that of Cape Cross was carried off by Captain Becker in 1893, and has found a last resting-place in the Museum of the `Institut für Meereskunde' in Berlin. The German Emperor has since caused an exact copy of it to be erected on the spot.

If we may trust to a legend upon a Map of the World drawn in 1489 by Henricus Martellus Germanus,(9) a legend confirmed by a `Parecer' drawn up by the Spanish pilots and astronomers who attended the `Junta' of Badajoz in 1524,(10) Diogo Cão died near this Cape Cross. And if Cão died, the details given by Ruy de Pina and Barros of the final stage of this expedition-the interview with the Mani Congo, who asked for priests and artisans, and sent Cazuto with gifts of carved ivory and palm-cloth to Portugal as his ambassador-must be rejected. I am inclined to believe that these details refer to Bartholomew Dias. Cazuto would then have reached Portugal in December 1488, was baptized at Beja in January 1489, when the King, his Queen, and gentlemen of title acted as sponsors, and was sent back to Congo with D. Gonçalo de Sousa, King John's ambassador, in December 1490.

But whatever the circumstances, Cão's name disappears henceforth from the annals of Portugal. His ships returned, no doubt, in the course of 1486, and when Dias started on his memorable voyage in August 1487 he took back with him the natives kidnapped by Cão on the coast beyond the Congo.

When an envoy of the King of Benin came to Portugal in 1485 or 1486 he roused the King's curiosity by giving him an account of a powerful ruler, far inland, who held a position among the negroes not unlike that held by the Pope in the Christian world. The King hastily concluded that this Ogane, as he was called, could be no other than the long-sought Prester John. He at once sent messengers by way of Jerusalem and Egypt in search of him, and prepared an expedition to aim at the same goal by sailing round Africa. The command of this expedition was given to Bartholomew Dias de Novaes, who departed from Lisbon in July or August 1487. He followed the coast to the south, and before the year had closed arrived at a Cabo da Volta and a Serra Parda at the entrance of a capacious bay, originally called Golfo de S. Christovão, but since known as Angra pepuena and Lüderitz Bay. Here, in lat. 26° 38' S., he set up his first pillar, fragments of which may now be seen at Lisbon and in the Cape Town Museum.

Proceeding onward, Dias, for a time, ran along the coast, but before he reached St. Helena Bay he had lost sight of the land. He thus sailed as far as 45° S., and, having apparently weathered a storm, stood east, but failing in the course of several days to meet with land, turned his prow to the northward. Sailing in that direction for 150 leagues, he saw lofty mountains rising before him, and on February 3, 1488, the day of St. Braz, he came to anchor in a bay which he called Bahia dos Vaqueiros (Cowherd's Bay). It is the Mossel Bay of our days.

During his onward course Dias had to struggle against the Agulhas current, as also against the prevailing southeasterly winds, and his progress was slow. He entered the Bahia da Roca (Rock Bay), now known as Algoa Bay, and 30 miles beyond it on an islet at the foot of a cape still known as Cape Padrone, he erected his second pillar, no trace of which has yet been discovered. When Dias reached the Rio de Infante (Great Fish River), and with it the threshold of the Indian Ocean, his crews refused to go any further. He turned back reluctantly, and on this homeward voyage he first beheld the mountains which fill Cape Peninsula, and at their foot set up his third and last padrão. According to tradition he named the southern extremity of this peninsula Cabo tormentoso, in memory of the storms which he had experienced, but King John, whose hope of reaching India by this route seemed on the eve of realization, re-named it Cabo da boa esperança-the Cape of Good Hope. We do not know whether Dias, on his homeward voyage, called at the Congo. We know, however, that he touched at the ilha do Principe, did some trade at a Rio do Resgate,(11) and called at S. Jorge da Mina. Ultimately, after an absence of sixteen months and seventeen days, he once more entered the Tagus. This was in December 1482.(12)

Voyages to the Guinea coast were of frequent occurrence at that time, and there is no reason why Behaim should not have been permitted to join one of these, either as a merchant or as a volunteer anxious to see something of the world. Most of these voyages were made for commercial purposes, but in addition to merchant-men there were Royal ships in the preventive service,(13) and surveying vessels charged with a more minute examination of the coast and the inland waters than had been done by the pioneer explorers. One of the most famous of these surveyors was the heroic Duarte Pacheco Pereira, the author of the `Esmeraldo de Situ orbis.'(14)

We have particulars of only two expeditions of this kind. The first of these I have already noticed. It was accompanied by José Vizinho, the astronomer.(15) The second was led by João Affonso d'Aveiro, who had been associated with Diogo d'Azambuja in the building of S. Jorge da Mina.(16)

The information concerning this voyage is fragmentary and leaves much to conjecture. J. A. d'Aveiro started in 1484, and he or his ship returned in the following year with an ambassador of the King of Benin, and the first Guinea pepper or pimento de rabo seen in Portugal, and sensational information about a king, Ogane, living far inland and rashly identified with the Prester John so long sought after. Upon receiving this news the King of Portugal ordered a factory to be established at Gato, the port of Benin, but the climate proved deadly to Europeans, many of the settlers fell victims to it,(17) and the place was abandoned. King John, at the same time, sent Fr. Antonio of Lisbon and João of Montarroyo to the east to inquire into the whereabouts of Prester John,(18) but, being ignorant of Arabic, they failed in their mission, whereupon, on May 7, 1486,(19) he despatched João Pero de Covilhã and Affonso de Paiva on the same errand.

Behaim has transmitted two accounts of the voyage along the west coast of Africa which he claims to have made, and on the strength of which posterity has dubbed him `the Navigator.' The first and more ample of these accounts may be gathered from the legends of his Globe and the geographical features delineated upon it.

The second account has found a place in the `Liber chronicorum,' compiled at the suggestion of Sebald Schreyer(20) by Dr. Hartmann Schedel, (21)printed by Anton Koberger and published on July 12, 1493, on the eve of Behaim's departure from Nuremberg. The original MS. of this work, in Latin, still exists in the town library of Nuremberg, as also the MS. of a German translation which was completed on October 5, 1493, by George Alt, the town-clerk. The body of the Latin MS. is written in a stiff clerk's hand, and is evidently a clean copy made from the author's original. The paragraph referring to Behaim has been added in the margin, in a running hand. In the German translation, f. 285a, this paragraph is embodied in the text. This proves that this information was given to the editor after he had completed the Latin original of his work, but before George Alt had translated it. Behaim at that time was still at Nuremberg, and there can be no doubt that it was he who communicated to Dr. H. Schedel this interesting information, and is responsible for it.

I shall now give the Story of the Voyage as it may be gathered from the Globe. It is as follows:

In 1484 King John of Portugal despatched two caravels on a voyage of discovery with orders to proceed beyond the Columns of Hercules to the south and east. Of this expedition the author of the Globe was a member. The caravels were provisioned for three years. In addition to merchandise, for barter, they carried eighteen horses, with costly harness, as presents for Moorish (negro) kings, as also samples of spices which were to be shown to the natives.

The caravels left Lisbon, sailed past Madeira and through the Canaries. They exchanged presents and traded with Bur-Burum, and Bur-ba-Sin, Kings of the Jalof and Sin, on the north of the Gambia, stated to be 800 German miles(22) from Portugal. Grains of Paradise were found in these kingdoms. Notice was taken of the current which beyond Cape Verde flows strongly to the south. The caravels then followed the coast to the east, past the Sierra Leoa (Sierra Leone), the Terra de Malagucta, the Castello de ouro (S. Jorge da Mina) and the Rio da lagoa (Lagos) to King Furfur's Country, "where grows the pepper discovered by the King of Portugal, 1485," and which is 1,200 leagues from Lisbon.(23) "Far beyond this" a country producing cinnamon was discovered. The place names along this part of the coast, such as Rio de Bohemo (Behaim's river) are absolutely original, and are not to be found on any Portuguese chart. It is to be regretted that the original delineation of the bottom of the Bight of Biafra, including the island of Fernando Po, should have been destroyed, for what we now see is merely the work of a restorer.

The islands in the Gulf of Guinea-S. Thomé, do Principe and the Insule Martini-were "found" by this expedition, and they were then without inhabitants.

Sailing southward along the coast the explorers passed the "Rio do Padrão," a "rio poderoso" or "mighty river" (lat. 25° S.), distinguished by a flag placed on its northern bank, until they reached a Monte negro, in lat. 37° S., the extreme Cape of Africa, where they set up the columns of the King of Portugal on January 18, 1485.

Doubling this Cape the explorers sailed about 220 leagues to the east, as far as a Cabo ledo (lat. 40° S.) 2300 leagues from Portugal, and having set up another column they turned back, and at the expiration of 19 months(24) they were once more with their King. A miniature of this cape shows the two caravels of the expedition. The distance from Portugal, as measured on the Globe, actually amounts to 2300 leagues.

I now proceed to give the story of Behaim's voyage as given in Schedel's `Chronicle.' After a reference to Prince Henry's discovery of Madeira and of the islands of St. George, Fayal and Pico, one of which was settled by "Germans of Flanders," the `Chronicle' continues as follows:-(25)

"In the year 1483(26) John II., King of Portugal, a man of lofty mind, despatched certain galleons (galeas), well found, on a voyage of discovery to the south, beyond the Columns of Hercules, to Ethiopia. He appointed two patrons (captains) over them, namely Jacobus(27) canus, a Portuguese, and Martinus Bohemus, a German, a native of Nuremberg in Upper Germany, of good family, who had a thorough knowledge of the countries of the world and was most patient of the sea (situ terre peritissimum marisque patientissimum), and who had gained, by many years' navigation, a thorough knowledge beyond Ptolemy's longitudes to the west.(28)

"These two, by favour of the gods, sailed, not farfrom the coast, to the south, and having crossed the equinoctial line entered another world (alterum orbem) where looking to the east their shadow fell southwards, to the right.(29) They had thus by their diligence, discovered another world (alium orbem) hitherto not known to us, and for many years searched for in vain by the Genoese. Having thus pursued their voyage they came back after twentysix months (30)to Portugal, many having died owing to the heat. As evidence of their discovery they brought with them pepper, grains of paradise, and many other things, which it would take long to enumerate. A great quantity of this pepper was sent to Flanders, but not being shrivelled like the oriental pepper and of a longish shape, preference was given to the true pepper."

These two accounts may be combined as follows:

In 1484 two caravels, commanded by Diogo Cão and Martin Behaim, were despatched by King John. They traded with the Jalof and the people of the Gambia, and sailing east "found" the Guinea Islands, including the Insula Martini. Having crossed the Equator, a feat attempted in vain by the Genoese for many years, they discovered another world. Sailing south as far as 37°, they reached a Monte negro, the extreme Cape of Africa, where, on January 18, 1485, they set up a column. Doubling this cape they sailed east another 260 leagues, as far as Cabo Ledo, when they turned back. King Furfur's Land, where grows the Portuguese pepper, seems to have been visited on the homeward journey in 1485. After an absence of 19 (26 or 16) months, they were once more at Lisbon, having suffered heavy losses from the great heat, and bringing with them grains of paradise, pepper and probably also cinnamon (said to have been discovered beyond King Furfur's Land) in proof of the discoveries they had made.

It is quite conceivable that Behaim's townsmen in the centre of Germany believed this account of his African voyage, but Behaim himself must have been aware that he was misleading them with a view to his own glorification. Even though he had made no voyage to the Guinea coast at all, and took no special interest in geographical exploration, he must have known that the islands of Fernando Pó, do Principe and St. Thomé, as well as the Guinea coast as far as the Cape of Catharina in latitude 1° 50' South,(31) had been discovered in the lifetime of King Affonso, who died in 1481. Genoese, and also Flemings,(32) certainly took a small share in the trade carried on along the coast discovered by the Portuguese, but since the days of Teodosio Doria and the brothers Vivaldi, in 1291, no Genoese vessels had started with a view of tracing the coast of Africa beyond the Equator. Behaim, if he really joined Cão in an expedition to Africa, must have known that his companion, in 1482, had discovered a mighty river and the powerful kingdom of the Mani Congo, and that in the course of a second expedition, in 1485, Cão traced the coast as far as a Cabo do Padrão, quite six degrees beyond the Monte negro of his globe. He must have known that Dias, in 1488, returned with the glorious news that he had doubled the southern cape of Africa, 12 degrees to the south of this padrão, and explored the coast for 120 leagues beyond, when the ocean highway to India lay open before him. Behaim is silent with reference to these facts, and any person examining his globe, and not conversant with them, would naturally conclude that it was Behaim, and his companion Cão, who first doubled the southern cape of Africa.

As to the grains of paradise, the pepper and also cinnamon, which were brought to Lisbon as "evidences" of discovery, a few words may be said.

Grains of Paradise, or Malaguetas, are the seeds of Amomum granum Paradisi, Afz, and as early as the thirteenth century this condiment reached Barbary and Europe by caravans crossing the Sahara.(33) Their discovery on the coast of Guinea dates back to the days of Prince Henry.

The pepper of King Furfur's Land or Benin is the pimenta de rabo, or "tailed" pepper, which Portuguese historians tell us was first brought to Portugal by João Affonso d'Aveiro. It is the fruit of Piper Clusii, D.C. The discovery of this pepper caused a sensation, for pepper, up till then obtained from India by way of Venice, was a costly spice-"ter muita pimenta," pepper is dear, is still said proverbially. Unfortunately this Guinea pepper was not highly valued in Flanders. King John told Dr. Monetarius (l. c., p. 68) that he believed the superiority of the pepper of Malabar and Sumatra to be due to the treatment of the berries, and that he had sent an expert to Cairo to enlighten him on the subject. After the discovery of India, when the trade in pepper became a Portuguese monopoly, the export of this pimenta de rabo was prohibited, in order that the high price of Oriental pepper might be maintained.(34)

Cinnamon is not found in Africa at all, except where its cultivation has been introduced in recent times from Ceylon. O. Dapper, however, the learned Dutch physician, apparently supports Behaim's statement as to cinnamon, for he says(35) that "black cinnamon" is found in Loango and is used for the purpose of "divination" (probably in the poison ordeal). I have searched in vain for an authority for such a statement. Mr. R. C. Phillips and Mr. R. E. Dennett, both men of education and of inquiring minds, who resided for many years as merchants to the north of the Congo, know nothing about "black" cinnamon. Of course, there are several species of Cassia, such as the Cassia occidentalis, the bitter root of which is antifebrile, whilst the roasted seeds furnish the "Negro coffee" of the Gambia; Cassia obovata, which yields senna, and other species. The bark, a decoction of which is most generally in use in the poison ordeals, is furnished by the Erythrophlaeum guineense, Don., a tree found in all parts of Africa, from the Senegal to the Zambezi.(36)

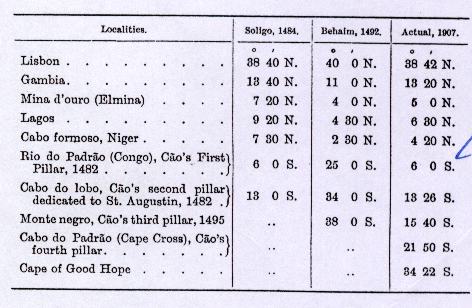

I now proceed to examine more closely the delineation of the west coast of Africa as given on the Globe, with special reference to the voyages of Cão, and of other expeditions of the period. I first of all compare the longitudes of a few places as found on a map of "Ginea Portugalexe," in all probability drawn by Christopher Soligo of Venice, and on Behaim's Globe with what they really are according to modern observations. Soligo's map is contained in a codex, which originally belonged to a Count Cornaro-Piscopi, then found its way into the Palace of the Doges, and may now be consulted in the British Museum, where it is labelled Eg. 73. The codex contains 35 charts by various draughtsmen, or rather copyists. The chart of " Ginea Portugalexe" which concerns us is in three sheets, and depicts the entire coast from Portugal to the "Ultimo padrão" set up by Cão on Cape St. Mary in latitude 13° 16'. Its Portuguese original was evidently drawn immediately after Cão's return from his first voyage in 1484. The chart is furnished with a scale, but is still without parallels. A legend written right against the mouth of the Niger tells us " hic non apar polus," but this invisibility of the pole-star is not borne out by the scale of the chart, for if we place Lisbon, according to Ptolemy, in latitude 38° 40' N. and allow 75 miglie(38) to a degree, the latitude of the mouth of the Niger would be 7° 30' N.

The next table gives the distances between certain localities according to the same authorities and as measured on a rather rude map of the world by Henricus Martellus Germanus.(39) This map is one of many in a manuscript codex, "Insularium illustratum," now in the British Museum (Add. MS. 15,760). It is dated 1489 and shows the discoveries up to the return of Dias in 1488. There is no scale, and in estimating the distances I have assumed the Mediterranean to be 3,000 Portolano miles in length.

On examining the above tables it will be found that whilst along the Guinea coast, from the Gambia to the Cabo formoso (Niger), the latitudes differ from the truth to the extent of only about two degrees, and the excess in distances only amounts to 20 per cent., these errors rapidly increase as we follow the coast to the south. The island of S. Thomé,(40) the true latitude of which is 15' N., is placed by Behaim in lat. 7° 30' S, while the River Congo is placed 19°, the Monte negro 22° 20' beyond the true position; the distance as measured on the Globe exceeds the truth to the extent of over a hundred per cent.

If we now turn to the delineation of South Africa on the Globe we cannot fail being struck with its general resemblance to the map of Henricus Martellus. It is only on comparing the nomenclature of the two that we discover striking differences. We then discover that the Monte negro which Behaim places in lat. 38° S. is not the Cavo de sperança of Martellus, as has been rashly supposed by certain critics,(41) but corresponds to the Monte negro of the latter, which we know to be in lat. 15° 40' S. It was upon this cape that Cão, in the course of his second voyage, erected one of his padrões, which has been discovered since in situ. We find further that the cavo ledo and San bartholomeo viego of the Globe, which seem to mark the furthest reached by Dias in 1487, are in reality meant to represent the furthest reached by Behaim himself when he sailed in the company of Cão in 1485.(42)

The place names along the coast to the south of the Cabo de S. Catharina as far as the Monte negro agree, as a rule, with the names to be found on the few surviving charts of the age of the Globe. A few names are peculiar, but this is natural, as the small scale on which these maps are drawn made it impossible to introduce every name to be found on the original charts, and copyists or compilers did not agree in the selection they made. It is remarkable, however, that the name of the famous kingdom of Congo should be looked for in vain upon the Globe, although its discovery and the establishment of intercourse with its powerful ruler constituted the most important event of Cão's two voyages, and an embassy from him was staying in Portugal when Behaim left for Nuremberg. It is curious, too, that the flag at the mouth of the Rio do Padrão should fly from the north bank, when any visitor to the river must have known that Cão's padrão was erected to the south.

Once we have doubled the Cape of Monte negro the place names are as puzzling as the names inserted upon Juan de la Cosa's chart,(43) which are supposed to represent the nomenclature bestowed by Vasco da Gama. Close to Cabo Ledo there is a Rio do requiem, which seems to owe its name to some tragedy, such as Cão's supposed death. Other names remind us of the voyage of Bartholomew Dias. A Rio do Bethlehem takes the place of Juan de la Cosa's Rio da Nazareth; the Angra de Gatto may represent the Angra das Vaccas of the same author, for as Behaim writes "patron" instead of "padrão" he may fairly be supposed to have written "gatto" (cat) instead of "gado" (cattle); the "Rio dos Montes" reminds us of the "terra dos montes," the Roca of the "baia da Roca" (Algoa Bay) of Cantino's chart. Lastly there is the enigmatic "San bartholomeo viego" and an Oceanus maris asperi meridionalis," which has been supposed to be connected with the gales experienced by Bartholomew Dias when doubling the Cape of Good Hope.

If we leave the South and direct our attention to Upper Guinea we shall find that, although the coast lines are drawn but roughly, there are not wanting indications that the author of the Globe had some personal knowledge of this part of Africa. He alone knows the name of the king from whose country pepper was brought to Portugal in 1485. "King Furfur's Country" is undoubtedly Benin, and if Behaim has placed the legend referring to it about a hundred leagues inland he did so only for want of space. Behaim, elsewhere, states that King Furfur's Country is at a distance of 1,200 leagues from Portugal, and this distance, measured on the Globe, carries us a hundred leagues beyond the Rio do lagoa (Lagos), as far as a Rio de Behemo (Behaim river), an appellation undoubtedly intended to point out the discoverer of the river, but absolutely ignored by all his contemporaries.(44) It is, however, more likely that merely new names were given to rivers previously discovered. For on Soligo's "Ginea Portugalexe" (1484) fourteen rivers are shown between the Rio dos Ramos and the Rio dos Camarões, including a Rio de S. Jorge and a Rio de S. Clara to the west of the Cabo Formoso, and a Rio de S. Bartholomeu immediately to the east of it.

The islands in the Gulf of Guinea, we are told, were "found" by the vessels which the King sent forth from Portugal in 1484, but they were actually discovered, with the possible exception of Annobom, during the reign of King Affonso, who died in 1481.

Fernando Pó, a cavalier of the household of that King, discovered, about 1471, the ilha formosa which now bears his name.

The ilhas de S. Thomé and S. Antão (Antonio) were perhaps discovered by Ruy de Sequeira, on his return from the Cabo de S. Catharina, the last discovery made during the reign of King Affonso.(45) The revenues of S. Antão having been granted to Prince João, the future King John II., when nineteen years of age (i.e. in 1474), the island was re-named Ilha do Principe, the Prince's Island, and under that name it figures on the Globe, as on all the available maps of the period.

The captaincy of S. Thomé was granted to João de Paiva on September 24, 1485, and its earliest colonists arrived there on December 16 of the same year. He was succeeded, in 1490, by João Pereira; in 1493 by Alvaro de Caminha, who sent thither the children of Jews who had been expelled from Spain in 1492,(46) and "degradados" or convicts; and in 1498 by Fernão de Mello. King John, in a conversation with Dr. Monetarius, in 1494, spoke of this deportation, but Behaim, whose Globe was made in 1492, may refer to an earlier dcportation consequent upon the cruel persecution of the Jews which, instigated by the Pope, took place in Portugal in 1487.(47)

The Insula Martini of the Globe appears to have been named by Behaim in his own honour. It is undoubtedly identical with the Ilha do Anno bom. The omission of this island on Soligo's "Ginea Portugalexe," (48)which was drawn immediately after the return of Cão from his first voyage in 1484, does not conclusively prove that the island had not been discovered at that time, for Duarte Pacheco Pereira, the author of the `Esmeraldo de situ orbis,' who wrote his work after 1505, and had access to all official documents, was equally ignorant of its existence. (49)The existence of the island cannot, indeed, have remained unknown for any length of time to vessels trading to the Gulf of Guinea, for it lies within the equatorial current, which carries a homeward-bound vessel at a rate of from 20 to 50 miles daily to the westward. Already Ruy de Sequeira, returning from the Cabo de S. Catharina, may thus have passed within sight of it, for it is visible for over forty miles, whilst traders bound homeward from Benin or Bonny, and desirous of avoiding the tedious struggle against the strong current flowing eastward along the Guinea coast, would try to make all the southing they could, and having passed Prince's Island and St. Thomé, would cross the Line, one or two degrees beyond which they would be carried westward by the equatorial current. By this route the passage from Bonny to Sierra Leone has been accomplished in less than three weeks, whilst vessels keeping near the coast have been as long as three months. This southern course may frequently have taken a vessel within sight of Anno bom, and as most of these vessels were traders and not royal ships, this may account for the ignorance of official historians. Indeed, I believe that the island was sighted or "discovered" repeatedly without much notice being taken of the fact. Valentin Ferdinand, on the authority of Gonçalo Pirez, a Portuguese skipper, who had been engaged for years in the trade of S. Thomé, states that Anno bom was discovered on January 1, 1501 in a caravel of Fernão de Mello, the captain donatory of that island, when it was found that seven years previously a fishing boat with three negroes in her, only one of whom was still alive, had been carried thither by the currents from the river Congo.(50) This seems to have been the "official" discovery of the island, which has retained the name then bestowed upon it up to the present time, but it was not the "first" and real discovery, unless we reject the account of Behaim altogether, confirmed as it is by his Globe. Val. Ferdinand, in the MS. already frequently referred to, presents us with three rude maps of the island, each differing from the other to so great an extent that if it were not for the titles, or the place where these maps are found, they could not possibly be believed to refer to the same island. The first of these maps (numbered 1 in the accompanying Map 5) has already been published by Dr. S. Ruge;(51) tracings of the two others I owe to the kindness of Dr. G. von Laubmann, the Director of the Munich Library, where the MSS. are kept.(52) The first of these maps agrees, in its general features, with the delineation upon the Portuguese chart which Alberto Cantino caused to be designed at Lisbon for his patron, Hercules d'Este, in 1502. The second map bears the title "Ilha diogo Cam," which seems to show that Ferdinand, when he made that sketch, believed the island to have been discovered by Diogo Cão, or, at all events, to have been named in his honour. A third map of the `Ilho ano boo' has apparently been rejected by the author as untrustworthy, for he has drawn three lines of deletion across it. The marked differences in these three outlines are equally observable in the few charts drawn up to 1502 and still available. And these differences not only extend to the outline of Annobom, but also to the latitude assigned to it, and of its bearings and distances from S. Thomé and the Cabo de Lopo Gonçalves.(53)

These differences seem to justify the conclusion that the draftsmen or compilers of these early charts depicted the island from map sketches brought home by successive navigators, who sighted it from a distance, but did not think it worth while to examine it more closely, so as to enable them to depict the island as correctly as the other islands in the Gulf of Guinea had been depicted years before.(54)

Having thus dealt at considerable length with the history of discovery and early cartography of Western Africa I shall endeavour to summarise the results in as far as they throw light upon the voyage which Behaim asserts he made in company with Diogo Cão.

We may dismiss without hesitation Behaim's assertion that he was appointed "Captain" of one of the vessels which sailed in that expedition. Such a command would not have been given to a foreign merchant only recently arrived in Portugal, and absolutely ignorant of naval affairs. He might, however, have been permitted to embark as a "volunteer" or as a trader. If he accompanied Cão as "cosmographer," as is asserted by several of his biographers but nowhere claimed by himself, the results must have been exceedingly disappointing if we are to look upon the delineation of the west coast of Africa on his Globe as the outcome of his labours.

There is moreover the evidence of the "inscribed rocks" only recently discovered on the Congo (see p. 22). These prove conclusively that Behaim played no leading part in Cão's second expedition, and that if he accompanied it at all it must have been in a very humble capacity.

Behaim tells us that Cão and himself left Portugal in 1484, and returned after an absence of 16, 19 or 26 months. As Behaim only arrived in Portugal in June 1484 at the earliest, he cannot be supposed to have started before July. His return, consequently, would have taken place in October 1485, January or August 1486. What then becomes of the knighthood conferred upon him on "Friday, February 2, 1485," or of the deed of partnership signed at Lisbon on July 12, 1486 by F. Dulmo, the captain of Terceira, and João de Estreito of Madeira, anent an expedition in search of the island of the Sete Cidades which was to have been joined by a "cavalleiro alemão," whom Ernesto do Canto,(55) a very competent judge, identifies with Martin Behaim, he being the only German at that time in Portugal to whom this description would apply?

As a matter of fact, if we accept the dates given, Behaim cannot possibly have taken part in the second voyage of discovery commanded by Diogo Cão. That famous navigator, having returned from his first voyage, was at Lisbon in April 1484. He only started on his second voyage of discovery after June 1485,-perhaps as late as September. Are we to suppose that during the interval between his two voyages of discovery, say between June 1484 and August 1485, Cão paid another visit to the Congo, perhaps for the purpose of taking back the hostages whom he had carried off in 1483? There exists no record of such a voyage, and Behaim's own account and his Globe distinctly point to a voyage extending far beyond the point reached by Cão in the course of his first voyage. Of course, Behaim may have made a mistake in his dates, and if instead of 1484-5 we read 1485-6 he may indeed have accompanied Cão in his memorable second voyage. But here again Behaim's own statements render this most unlikely. Cão, being bound on a voyage of discovery, would naturally have made haste to reach the Congo. He certainly would not have delayed in the Gambia to get rid of his horses and their costly harness, or wasted time in tedious barter with Jalof and Sin. Neither is it likely that many of Cão's men died owing to the heat, which may well have happened to an expedition which stayed for some time in the Gulf of Guinea. Indeed, it was the great mortality among the Portuguese who were sent to Benin in 1486 which caused a factory occupied by them in that kingdom to be abandoned soon afterwards.(56)

Lastly there is the Guinea pepper, brought home in proof of the discoveries that had been made. In fine, all that Behaim tells us might have happened in connexion with a trading voyage, such as that of João Affonso d'Aveiro. If that Captain sailed in 1484 and Behaim joined his ship at the end of June or in the beginning of July, soon after his arrival in Portugal, he might have been back in Lisbon after an absence of seven months, in time to be knighted by the King in February 18,1485. A voyage to Benin and back would have occupied about four months, and there remained thus three months available for trading on the Gambia and elsewhere. Proceeding twelve leagues up the Rio Formoso, which according to D. Pacheco Pereira was navigable only for vessels of fifty tons burthen,(57) J. A. d'Aveiro reached Gato, the deadly climate of which carried off not only the leader himself but also many of his companions.(58) Having taken on board the ambassador of the King of Benin and a cargo of pimenta de rabo, the expedition left for Portugal. On the homeward route, when making for the serviceable equatorial current, the Insula Martini of the Globe was sighted. Lisbon was reached after an absence of only seven or eight months, and Behaim, in recognition of the services he had rendered, was knighted on February 18, 1485. But if we suppose d'Aveiro to have started only in 1485, immediately after this honour had been conferred upon Behaim, sixteen months might have been expended upon this voyage, and yet he would have been back in Lisbon in July 1486, in time to accede to the agreement about a proposed search for the island of the Sete cidades.

Having given this subject the most careful consideration, it is my belief that Behaim was not a member of Cão's expedition, but that he may have made, and probably did make, a voyage to Guinea, and that he probably did so on board the vessel of João Affonso d'Aveiro. The Globe with its legends and the account of his voyage given to the editor of the `Chronicle' were calculated to convey an idea that the expedition which he had joined was the first to cross the line into "another world," and ultimately doubled the southern cape of Africa. In Portugal, where the facts were known, he would not have dared to put forth such claims or such an incorrect delineation of the west coast of Africa. It was easy, however, to deceive the worthy burghers of his native town, who knew little or nothing about the maritime enterprise of the Portuguese, and looked upon their townsman as a great traveller, as indeed he was, and a successful discoverer, which he was not.

(1) For a fuller account of these explorations see my essay on `The Voyage of Diogo Cão and Bartholomew Dias' (`Geographical Journal,' Dec. 1900). Since writing this paper important rock inscriptions referring to Cão's second expedition have been discovered at the mouth of the river Mposo, near Matadi. back

(2) Antonio Galvão was born at Lisbon in 1503, spent 1527-47 in India, and died 1557 in hospital. His `Tratado' was published at Lisbon in 1563, and again, with a translation, by the Hakluyt Society (`The Discoveries of the World'), 1862. back

(3) D. Cão, in 1483, captured three Spanish vessels on the Guinea coast. For an account of this capture by Eustache de la Fosse of Doornick, see C. Fernández Duro, `Boletin,' Geographical Society of Madrid, 1897, pp. 193-5. back

(4) Ruy de Pina, `Chronica d'El Rey João II.,' c. 57. back

(5) Illustrated descriptions of these padrões are given by Luciano Cordeiro, `Boletim da Soc. Geogr. de Lisboa,' 1892 and 1895. back

(6) This change probably was ordered in June 1485 when a similar change took place in the coinage. (Teixera de Aragão, `Descr. geral e hist. das moedas,' Lisbon, 1874-83, I., p. 240; J. Pedro Ribeira, `Dissert. chronol. e criticas,' t. III. App. VI. and plates.) back

(7) For a description of this padrão see Scheppig, `Marine Rundschau,' 1894, p. 357, and `Die Cão-Säule am Kap Cross' (Kiel, 1903): L. Cordeiro, `O ultimo Padrão de Diogo Cão' (Boletim, 1895, p. 885). back

(8) 2 This important inscription was known in 1882, for on the map of the Lower Congo, by Capello and Ivens, is indicated a `Padrão Portuguez.' Father Domenjuz of Matadi seems to have been the first to have taken a photograph of it, which was published by L. Frobenius in his work `Im Schatten des Kongo Staates,' 1907. Another photograph, by the Rev. Pettersson, has been published by the Rev. Tho. Lewis (`Geogr. Journal,' xxi., 1908, p. 501). back

(9) For a reduced facsimile of this map see p. 67. For further information on this map, p. 66. back

(10) This `Parecer' or Report is printed in Navarrete's `Colleccion,' IV. (Madrid, 1837), p. 347. J. Codine, `Découverte de la côte d'Afrique' (Bulletin de la Soc. de Géogr., 1876, Notes 23 and 29), would have us believe that the words "et hic moritur" of the legend do not refer to Cão but to the Serra Parda. This is quite inadmissible. The Spanish pilots say "donde murio" where he died. back

(11) `Trade river'-perhaps the Rio formoso. back

(12) Dias in 1497 accompanied Vasco da Gama as far as the Cape Verde Islands; in 1500 he commanded a vessel in Cabral's fleet, and perished off the Cape which he had discovered. back

(13) It was in this service that D. Cão, in 1480, captured three Spanish interlopers. back

(14) For a biographical notice see p. 2, Note 5. back

(15) See p. 13. back

(16) Ruy de Pina, c. 94, Garcia de Resende, and J. de Barros, `Da Asia, Dec. I., Liv. III., c. 3, say that d'Aveiro returned from this voyage in 1486; according to A. Galvão he returned in 1485 or 1486; according to Correa, `Lendas,' t. I., c. 1, in 1484. According to A. Manuel y Vasconcellos, `Vida y acciones do Rey D. Juan II.' (Madrid, 1625), p. 165, and Manuel Telles da Silva, `De rebus et gestis Joanno' (Lisbon, 1689), p. 215, both Cão and d'Aveiro sailed in 1484. These dates, unfortunately, are not very trustworthy. back

(17) There is no doubt that d'Aveiro died in Benin, but whether his death happened in the course of the first voyage or after the establishment of the factory at Gato, is not made clear from the available narratives of the voyage. J. Codine (`Bull. de la Soc. de géographie,' 1876) believes that he died during the first voyage. back

(18) De Barros, `Asia,' Dec. I., Liv. III., c. 5. back

(19) Ruy de Pina, who may have been present when these messengers took leave of the King, says May 7, 1486 (c. 21), but Alvarez (l.c. c. 102) was told by Covilhã, whom he met in Abyssinia in 1521, that he departed on May 7, 1487. If Covilhã left Portugal in May, 1486, d'Aveiro's expedition must have returned in 1485, and such seems to have been the case, for Frei Fernando de Soledade (`Historica Serafica da ordem de S. Francisco,' t. III., Lisbon, 1705, p. 412) says that Frei Antonio of Lisbon and João (Pedro) de Montarroyo were despatched in 1485. back

(20) Sebald Schreyer, b. 1446, was a liberal supporter of art and science. It was at his suggestion that the `Liber chronicorum' was compiled, and he paid part of the cost of its publication. back

(21) Dr. H. Schedel was born 1440, settled at Nuremberg in 1488 and died there in 1514. He was an enthusiastic pupil of Conrad Celtes, and an indefatigable collector of codices and inscriptions. On f. 266 of the Latin edition H. Schedel is named the author or editor, on June 4, 1493, but at the end of the volume, f. 300, his name is omitted, and the following are named instead:-Seb. Schreyer, Sebastian Kammermeyster (mathematician), A. Koberger (printer), Michael Wolgemut and Wilhelm Pleydenwurff (draughtsman). M. Wolgemut, the famous artist, was born at Nuremberg in 1434, and the illustrations of the volume were executed in his workshop. back

(22) A gross exaggeration! From Lisbon to the Gambia is only 450 German miles, or, as measured on the Globe, 560 miles. back

(23) Of the identity of King Furfur's Country with Benin there can be no doubt. If we accept the date 1485 as correct, this country was discovered on the homeward voyage. Of course I know that "furfur" is the Latin for bran, and "fur" for thief or slave. back

(24) Nineteen months according to two legends on the Globe, one of them close to Cabo Ledo. back

(25) Latin original, f.290; German translation, f.385A. back

(26) A misprint for 1484 or 1485? back

(27) Jacobus, Diogo, James and Jack are synonymous. back

(28) This claim to be an experienced navigator is absurd, for Behaim's first experience of the sea was made in 1484. Of his further experience up to 1490, we know nothing. back

(29) The inhabitants of the tropical zone are, of course, Amphiscii, whose shadow at noon is thrown to the north or south according to the position of the sun. Behaim's statement is applicable only to inhabitants of the southern temperate zone. back

(30) In the Latin "vicesimo sexto mense," but in the German translation "in dem sechzehenten monat." Dias is said to have come back after an absence of 16 months 17 days. back

(31) Here, on the chart of "Ginea Portugalexe," 1484, is shown the "tree marking the furthest discovered in the time of Fernam Gomez," whose trading monopoly, granted in 1469, expired in 1474. back

(32) Pacheco Pereira, `Esmeraldo,' p. 54, tells us of a ship manned by thirty-four Flemings, which was wrecked on the Malagueta coast and its crew eaten up by the natives. back

(33) Conde de Ficalho, `Memoria sobre a Malagueta,' Lisbon (Academia das Sciencias), 1878. back

(34) Conde de Ficalho, `Plantas uteis da Africa Portugueza' (Lisbon, 1884), p. 245. back

(35) C. Dapper, `Africa' (German edition), Amsterdam, 1670, p. 511. Mr. Dennett is the author of `Seven Years among the Fjort' (London, 1887) and `Notes on the Folklore of the Fjort' (London, 1898). back

(36) Ficalho, `Plantas uteis,' pp. 157, 164. Also Dr. M. Boehr, `Correspon. der Deutschen Afrik. Ges.,' vol. I., p. 382. back

(37) See Map of Guinea and South-Western Africa compiled from materials available in 1492. Map 5. back

(38) The Portuguese Legoa of 7,500 varas was equal to 6,269 meters, and 4*24 Italian miglie of 1,480 meters each were therefore equal to one legoa. One degree of the Equator (111,307 meters) was consequently equal to 17*75 legoas or 75*21 miglie (or miles). Pilots generally assumed that 4 miles were equal to a league. Girolamo Sernigi, who wrote a letter to a gentleman at Florence about Vasco da Gama's first voyage, knew better, for he reckoned 4¼ Italian miles to a league, and on the chart which Alberto Cantino caused to be compiled at Lisbon, in 1502, for his patron, Hercules d' Este, Duke of Ferrara, a degree is equal to 75 miglie (see images, `A Journal of the First Voyage of Vasco da Gama,' pp. 208, 245). back

(39) Henricus Martellus (Heinrich Hammer) was evidently a German settled in Italy. A MS. Ptolemy in the Biblioteca Magliabechiana contains a map of modern Italy drawn by him (A. Mori, `Atti.-sec. Congr. Ital.,' Rome, 1896, p. 567). Facsimiles of his map of the world have been published by Count Lavradio (1863) and in Nordenskiöld's `Periplus.' back

(40) St. Thomé 2° 30' N. according to Soligo, 1° N. according to Pacheco Pereira (`Esmeraldo,' p. 15). back

(41) The "Caput bona spei" of Ghillany's and Jomard's facsimiles is not to be discovered on the Globe. back

(42) See p. 24. back

(43) Juan de la Cosa accompanied Columbus and Alonso de Hojeda on their voyages to the West, 1493-1500, and on his return he compiled the map which bears his name, and facsimiles of which have been published by Santarem, Jomard, A. Vassano and in Nordenskiöld's `Periplus.' J. de la Cosa was killed in a fight with Indians near Cartagena, 1509. back

(44) I fancy that this Rio de Behemo may be identical with the Rio Formoso, or river of Benin. back

(45) The Saints' days are, St. Catherine, November 25, St. Thomas, December 21, St. Anthony, January 17. back

(46) King John received these fugitives on condition of their paying a ransom and departing the kingdom within a limited time, on pain of being made slaves. back

(47) Ruy de Pina, c. 29. back

(48) See p. 26. back

(49) As was also Waldseemüller or Hylacomilus when he compiled his map of the world in 1507, and the modern maps which appeared in the Strassburg edition of Ptolemy in 1513. Waldseemüller was born about 1470 at Radolfzell, studied at Freiburg, and is the author of two large maps of the world only recently discovered and published by J. Fischer and F. R. von Wieser (the oldest map of the world with the name America, Innsbruck, 1903). He died in 1521. See L. Gallois (`Americ Vespucci,' 1900) and F. Albert (`Zeitschrift f. Gesch. des Oberrheins.' XV. 1901, p. 510). back

(50) `Bol. da Soc. de Geogr.,' Lisbon, VI., 1900, p. 353. back

(51) `27. Jahresb. des Vereins für Erdkunde zu Dresden,' 1901. back

(52) Cod. Hisp. 27 ff., 339r and 343r and V. back

(53) For Cantino see pp. 26 and 27. Nicolas de Canerio was a Genoese. Facsimiles of his map of the world have been published by Gallois (`Bull. Soc. de Géogr.,' Lyon, 1890) and G. A. Marcel, Keeper of the Cartogr. Collection of the Bibl. Nat. (`Reproduct. des Cartes et Globes,'&c.). The chart, now the property of Prof. E. T. Hamy of the Musée d'Ethnogr., Paris, was bought at the sale of the library of the late Captain King, London. Facsimiles have been published by Dr. Hamy himself and in Nordenskiöld's `Periplus.' back

(54) In proof of which see Map 5, insets. back

(55) `Arch. dos Açores,' I., p. 341, IV., pp. 440, 443. back

(56) De Barros, `Asia,' F. I., p. I., p. 179. back

(57) D. Pacheco Pereira, `Esmeraldo,' p. 72, had visited Gato four times, but refers neither to the factory established there nor to J. d'Aveiro. back

(58) I agree with J. Codine (`Bull. de la Soc. de Géographie,' Paris, 1869, II., and 1876, I.) that d'Aveiro died during the first voyage to Gato and not in the course of a second expedition after a factory had been established at the place. I cannot, however, accept the remainder of his speculations concerning the expeditions of Cão and d'Aveiro. He assumes both navigators to have started in October, 1484, both bound for south-western Africa. He credits Cão with having set up three padrões: the first on the Congo in 1485, the second (that of S. Agostinho, in 13° 23' S.) on August 15, 1486, the third at Cape Cross. J. A. d'Aveiro, who was accompanied by Behaim, is supposed to have set up two padrões, viz., one on Monte Negro in 15° 40' S., on January 12, 1485, as stated on the Globe, the second at Cape Frio, which he identifies with San Bartholemeu Viego, in August, 1485. Benin was visited on the homeward voyage, and the vessel returned to Lisbon in May, 1486. The death of d'Aveiro enabled Behaim to claim credit for an expedition in which he only held a sub- ordinate position. Cão came back to Lisbon in April, 1486. back

Back to Table of Contents

Last modified: Fri Feb 6 01:31:07 CET 2004